SVA graduate thesis, 2014 - 2015

Links: Thesis Blog, Final Presentation, Design Observer, SVA Products of Design Blog

This thesis project is a year-long exploration of memory, trauma, and natural disasters. Beginning as a project about memory, the focus shifted to trauma-specific after the research phase.

I Was There When explores how people deal with traumatic memories – more specifically, mental relief after natural disaster experiences. Given that the most fundamental thing designers do is make sense of a mess, the project’s challenge is to make sense of the most unexpected and uncontrollable mess there is – or rather, the psychological damage that lingers long after the physical rubble has been cleared.

Natural disasters are comprised of a highly complex ecosystem, and the beating heart is the disaster victim. What is natural only becomes a disaster when people are involved – when their homes are struck by a tornado, when they’re injured from a storm, or when they lose a spouse in a hurricane. And unfortunately, the earth kills 106,000 people per year, on average.

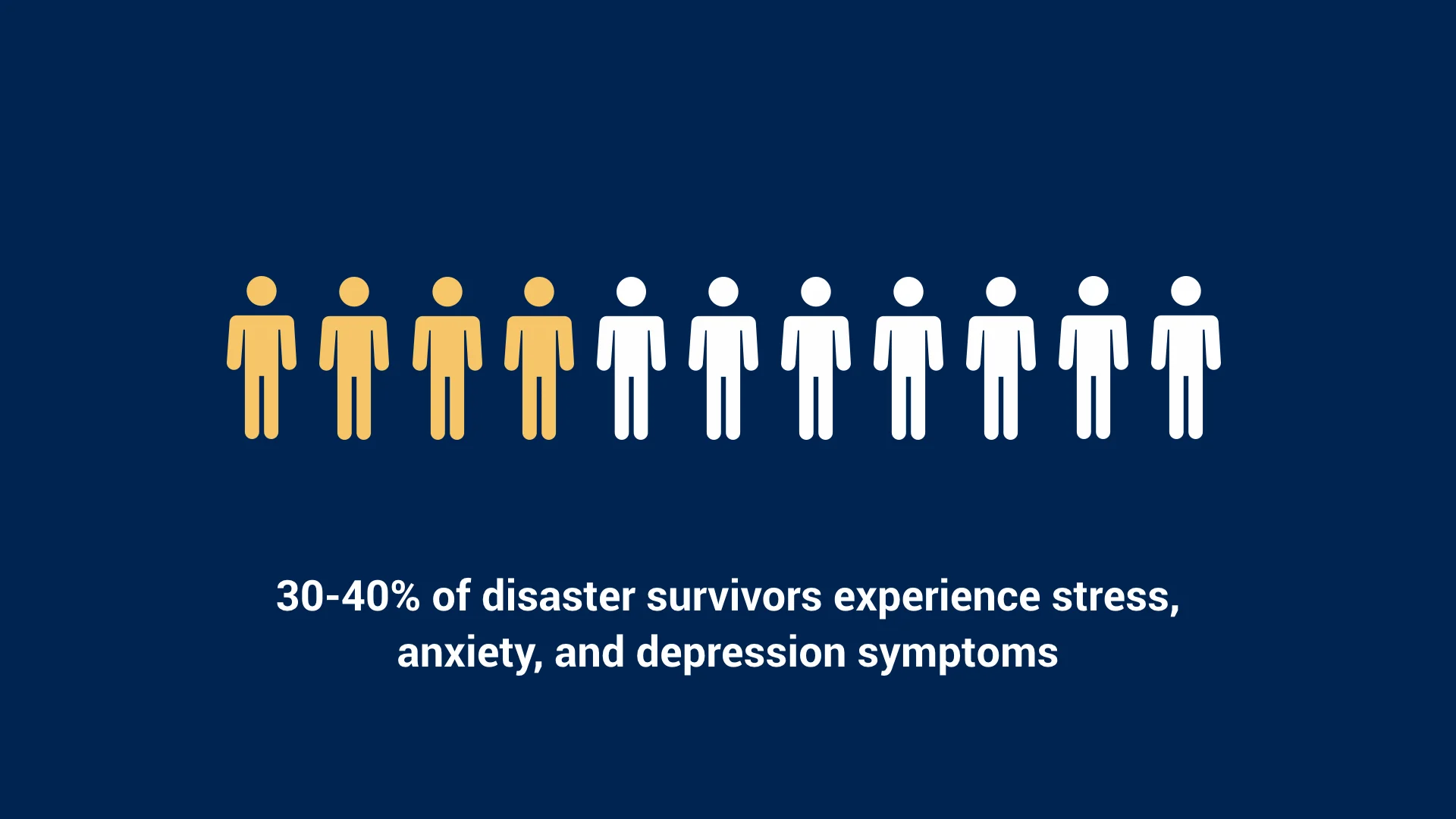

While it is evident that disasters result in a huge physical loss, the magnitude of destruction on the mental well-being of those who survive is just as detrimental. 30–40% of people affected by natural disasters will experience Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, or anxiety symptoms.

Research

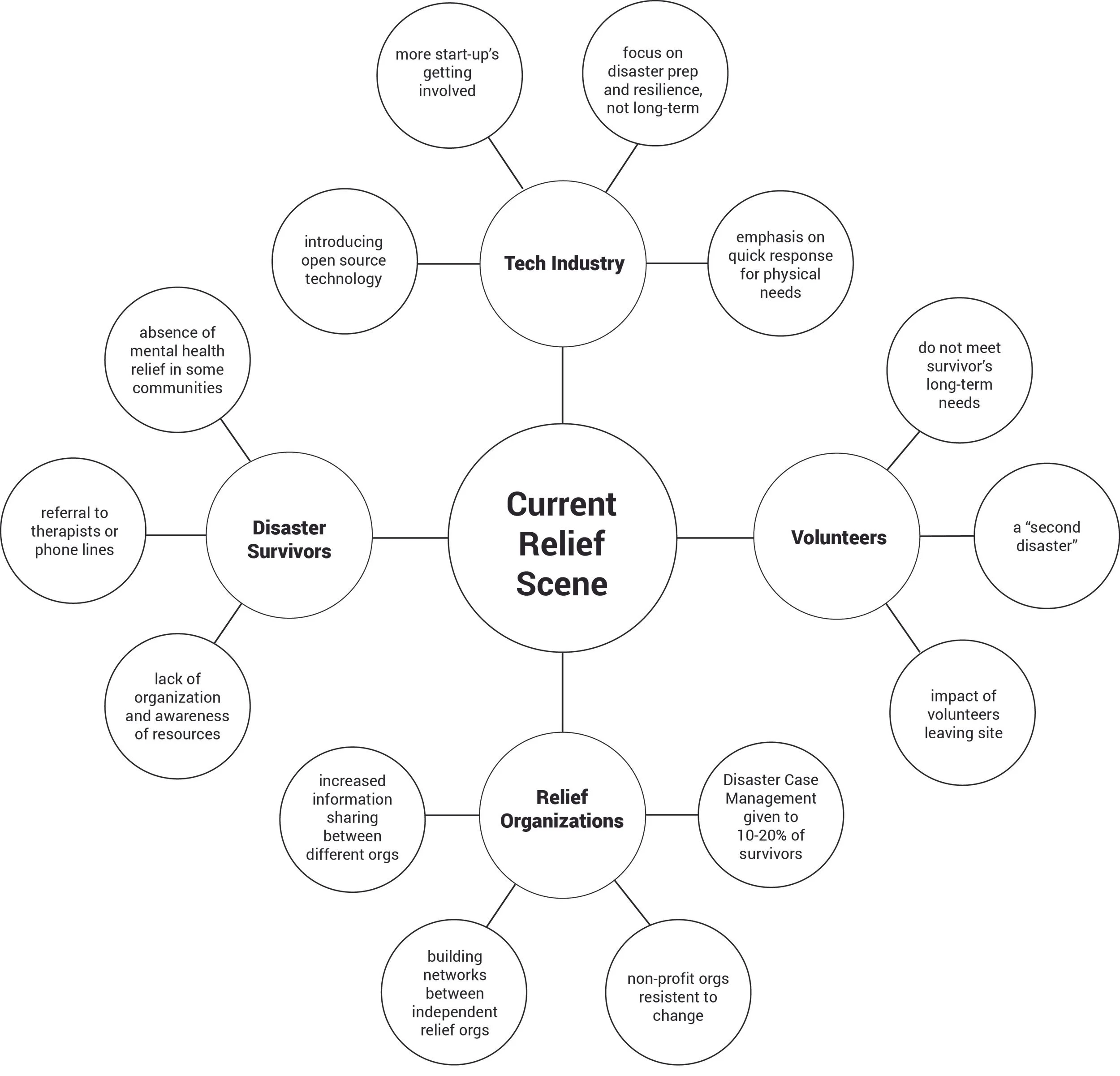

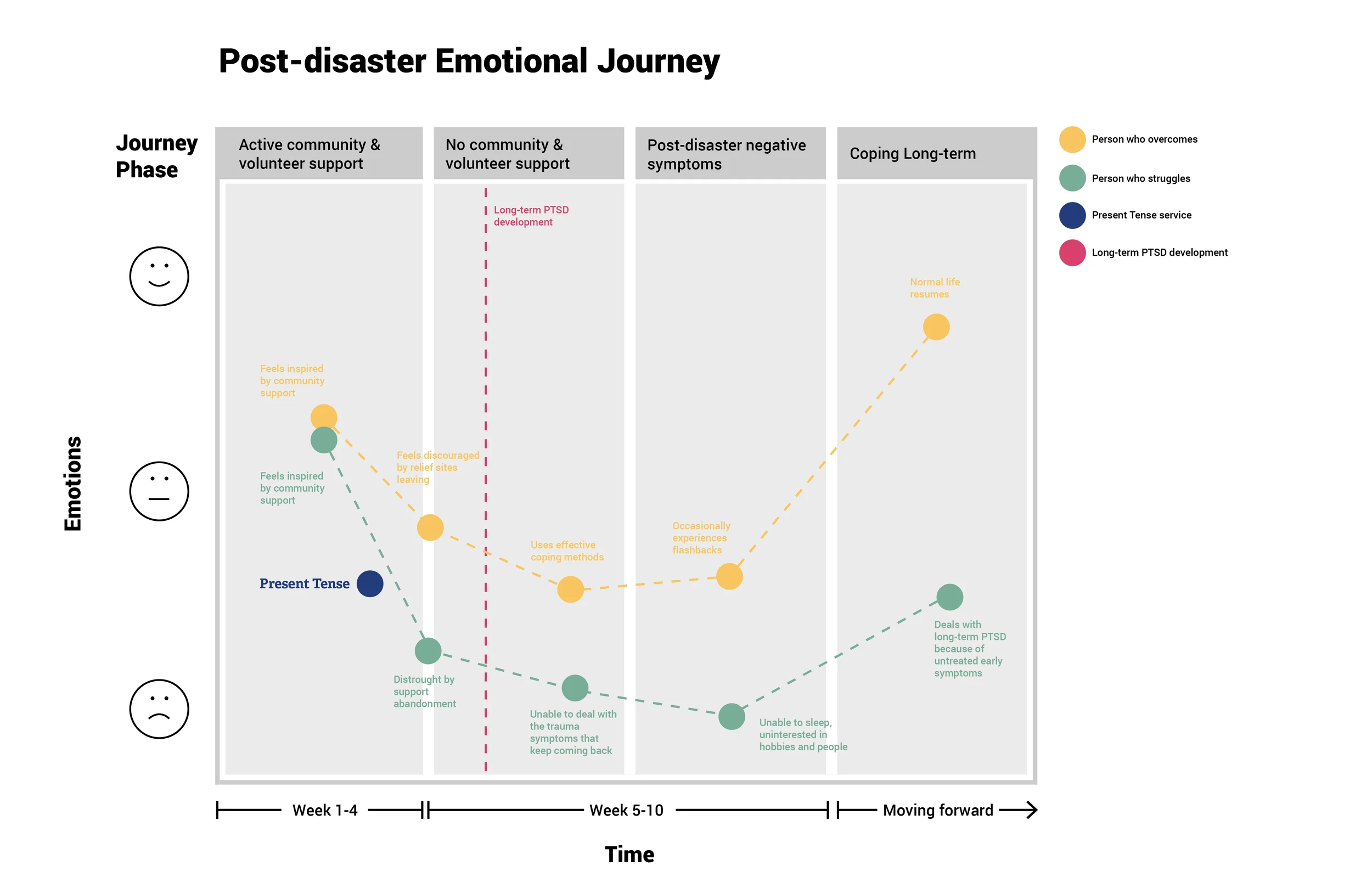

Through her research, Ayaydin learned that there’s a crucial period of time after a disaster where people are especially sensitive. This is also the time when community volunteers and relief organizations start to leave the disaster site. Nastaran Mohit, one of many volunteers that spoke about this key period of time, explained that people assume communities are bouncing back, but they’re not, and survivors feel a sense of abandonment. When trauma symptoms are not treated, some people fall through the cracks and develop PTSD.

Conversations with neurologists, psychologists, researchers, professors, people that have experiences around memory disorders, designers, and visionaries; disaster survivors and volunteers, and experts in relief organizations who work with disaster recovery everyday.

Living in a time where we are increasingly turning to “empowerment” for problem solving, Ayaydin asked the question, can we give people the agency to successfully cope with their traumatic experiences?

Research uncovered key principles that Ayaydin followed throughout her journey. One principle came from a documentary about music’s capacity to combat memory loss in Alzheimer’s patients. It quotes, “medicine can dim the light inside but it can’t bring any of it out.” It inspired her to incorporate the power of non-medical interventions into her work.

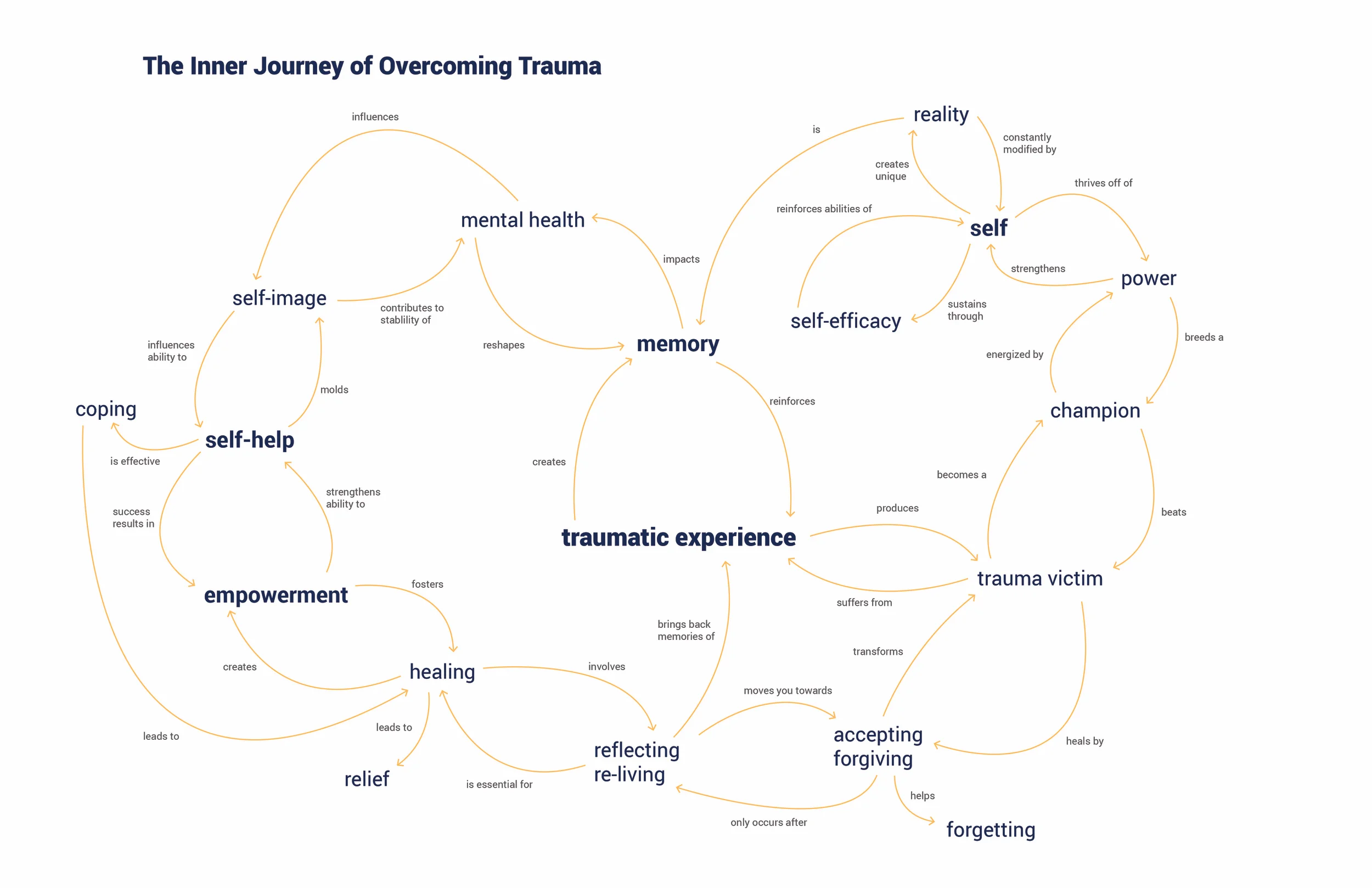

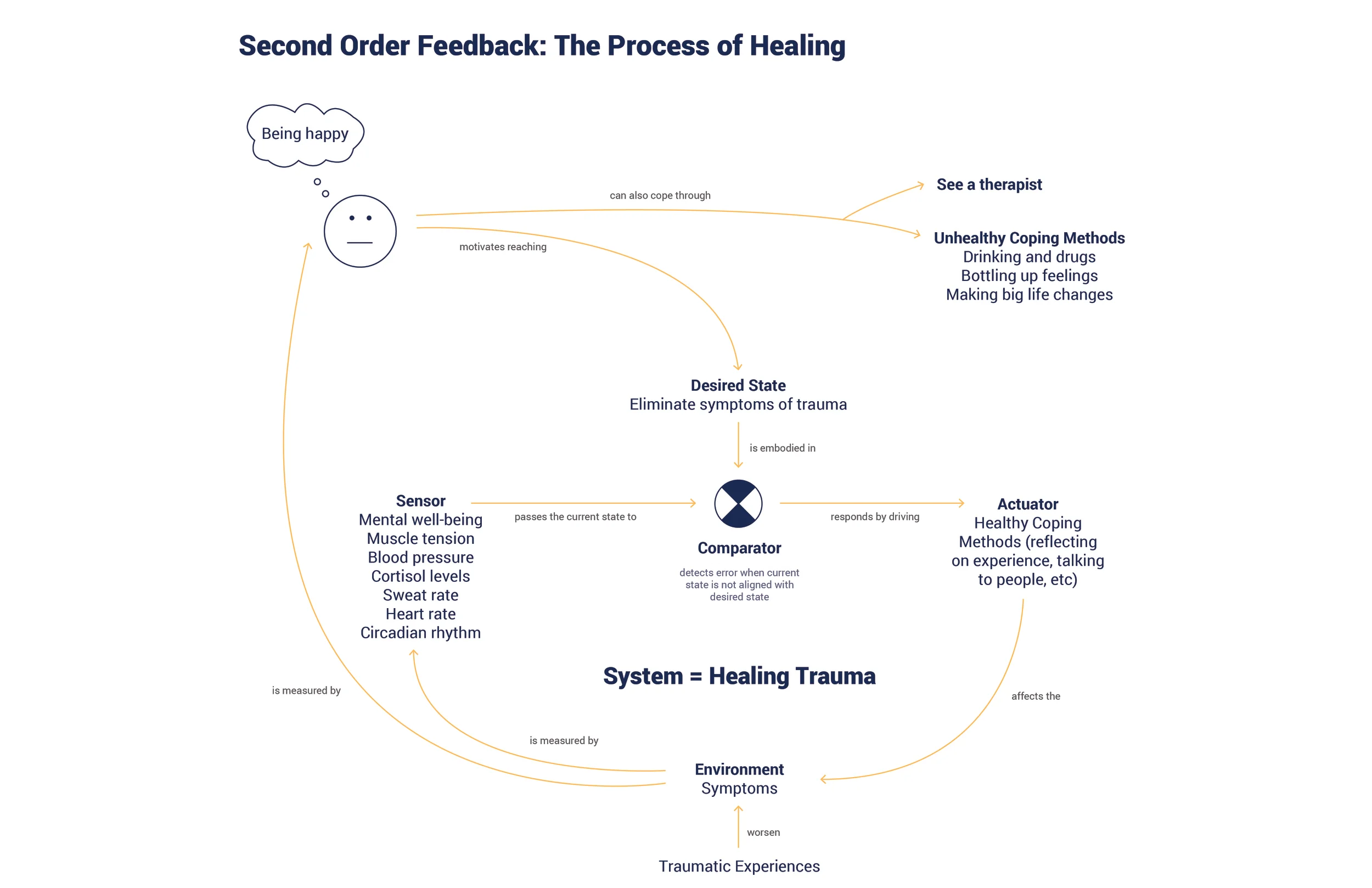

Using design as the bridge between science and the people, Ayaydin was inspired by a conversation with Barry Kosofsky, Chief Neurologist at Weill Cornell Medical Center, who explained that his recent studies show “extinction is not erasing old memory, but rather placing down a new one. This has tremendous implications for how we should treat people suffering from PTSD.” This conversation, in conjunction with other neurologist and memory researcher interviews, led to an insight that reveals something innate to humans: we’re always trying to remember, and we forget to forget. It turns out in order to heal, we must forget, and in order to forget, we must remember. Mapping out the journey of overcoming trauma quickly revealed this key part of the healing process – reflecting and reliving as a method of coping.

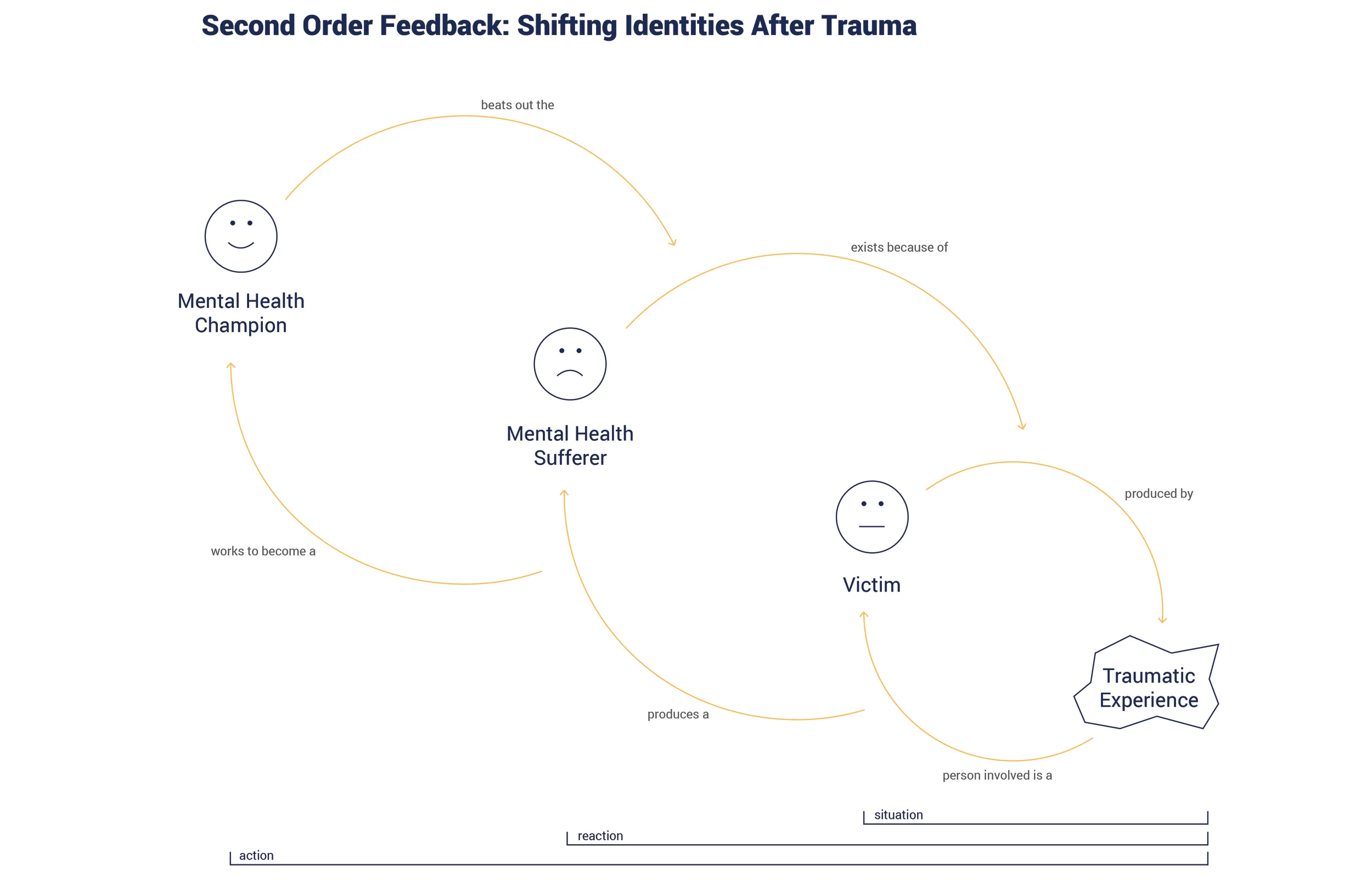

In addition to this, Post-Traumatic Stress has the potential to transform into Post-Traumatic Growth. Post-Traumatic Growth is when people experience a trauma that changes their worldviews and self-identities in a way that provokes positive personal growth. Essentially, “a traumatic event can be used as a spring board to unleash our best qualities and lead happier lives.”

It’s scientifically proven that people can increase their ability to experience post-traumatic growth by boosting 4 types of resilience, one of which is social resilience. Bringing this closer to natural disasters, a longitudinal study called Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) started before the hurricane hit and collected data that provided an extremely rare opportunity to study the consequences of a disaster, which reveal findings that people tend to feel this greater sense of purpose as a result of strong social support.

Initial Design Explorations

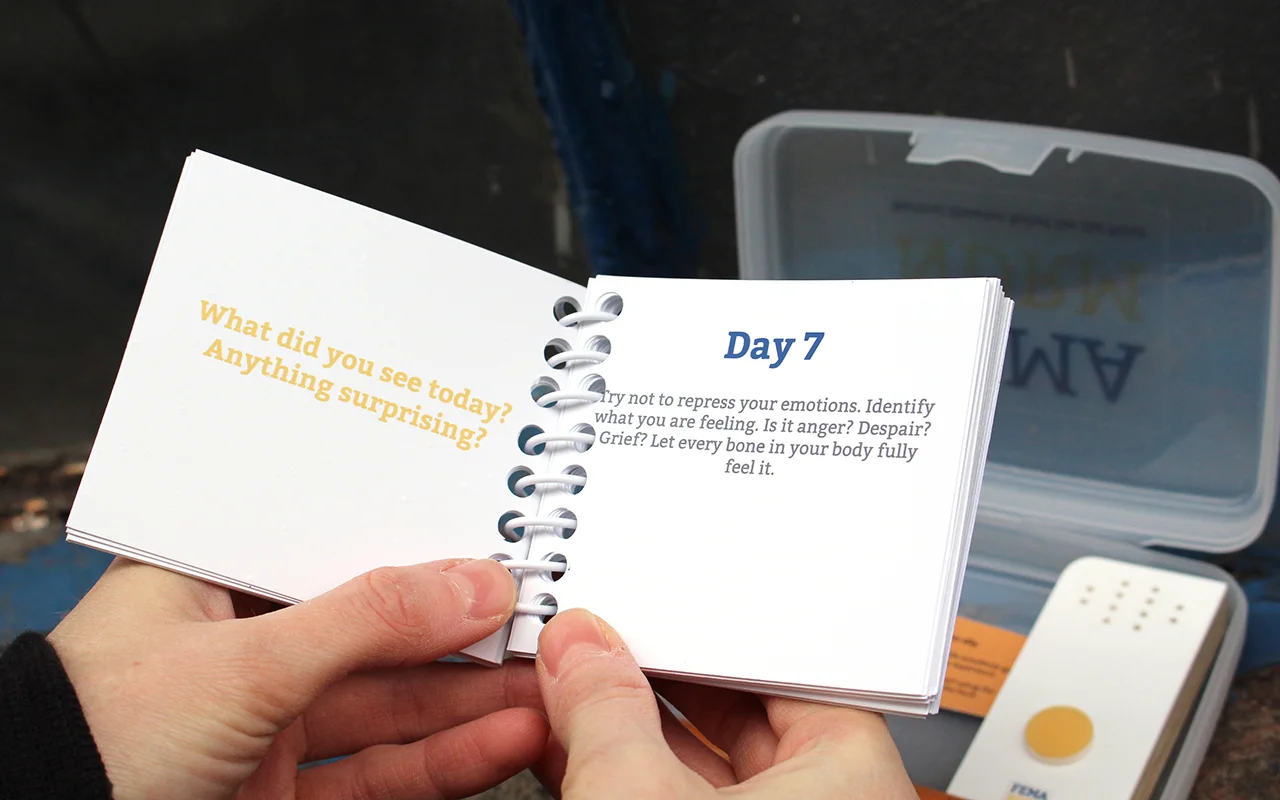

Having initially designed a physical service – a mental relief kit that takes into account the fact that people won’t have phones, internet, or power right after a disaster strikes - I eventually moved past designing for immediate response when physical needs are primary.

The Natural Disaster Relief for the Mind (NDRM) kit proposed here in I Was There When is first a service, starting with a kit that one receives after experiencing a disaster. This is not intended to be a catch-all, as what a disaster survivor needs to do during a tornado is very different than what they need during a hurricane, and the level of disaster each individual experiences is relative. Hence, this is a first round attempt at building a model that speculates what the primary needs of natural disaster victims are and how they can be addressed. The kit does, however, capture the overall goal and opportunity of this project, which is to empower people by giving them the tools they need to help themselves. Of course, a victim’s needs are dependent on the context of their situation. Also, it is clear that there are systemic limitations for both implementing a new service and distributing kits. The kit itself is a set of tools that address a hierarchy of needs.

Service Design

The strategy:

Concept development:

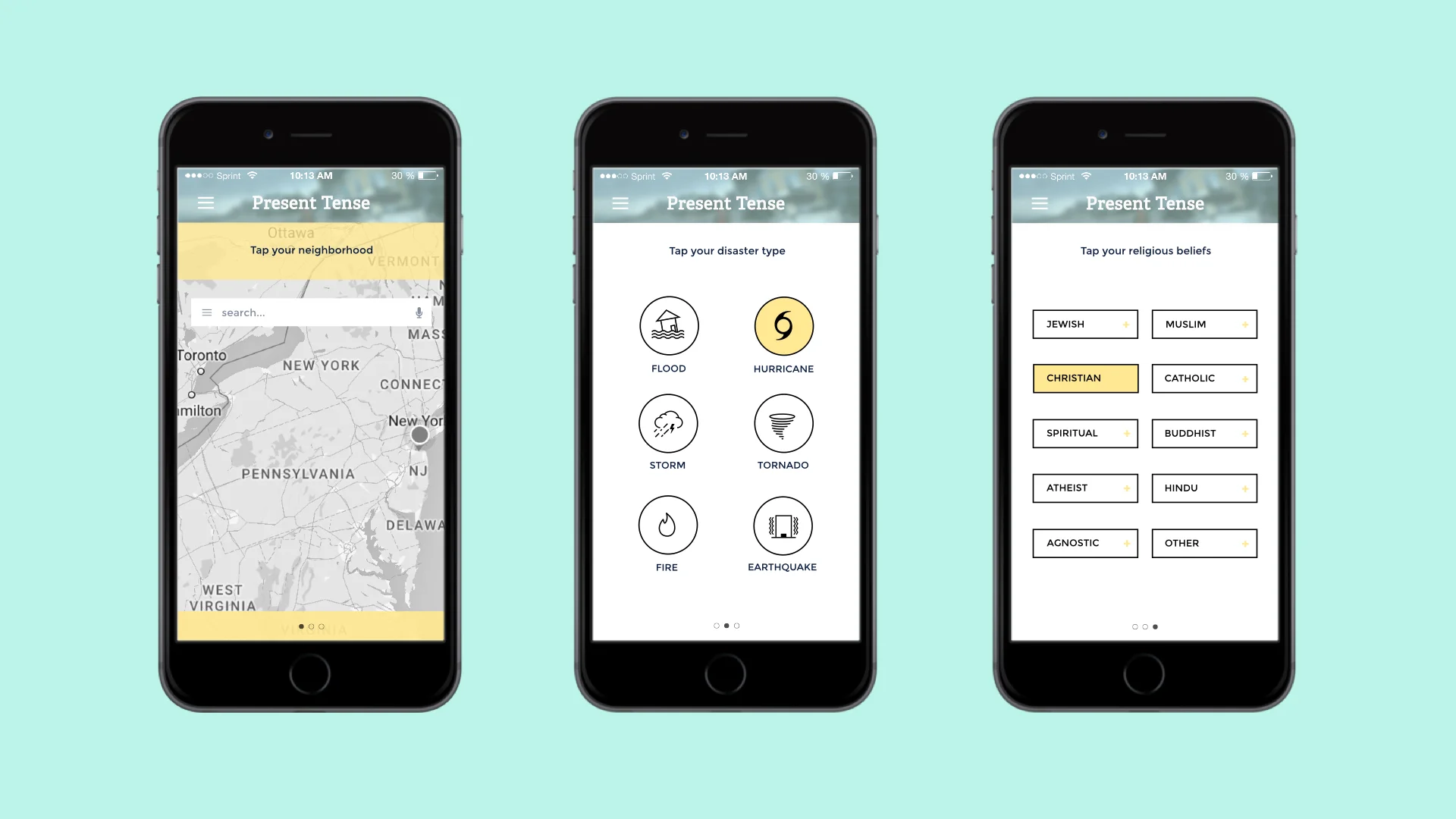

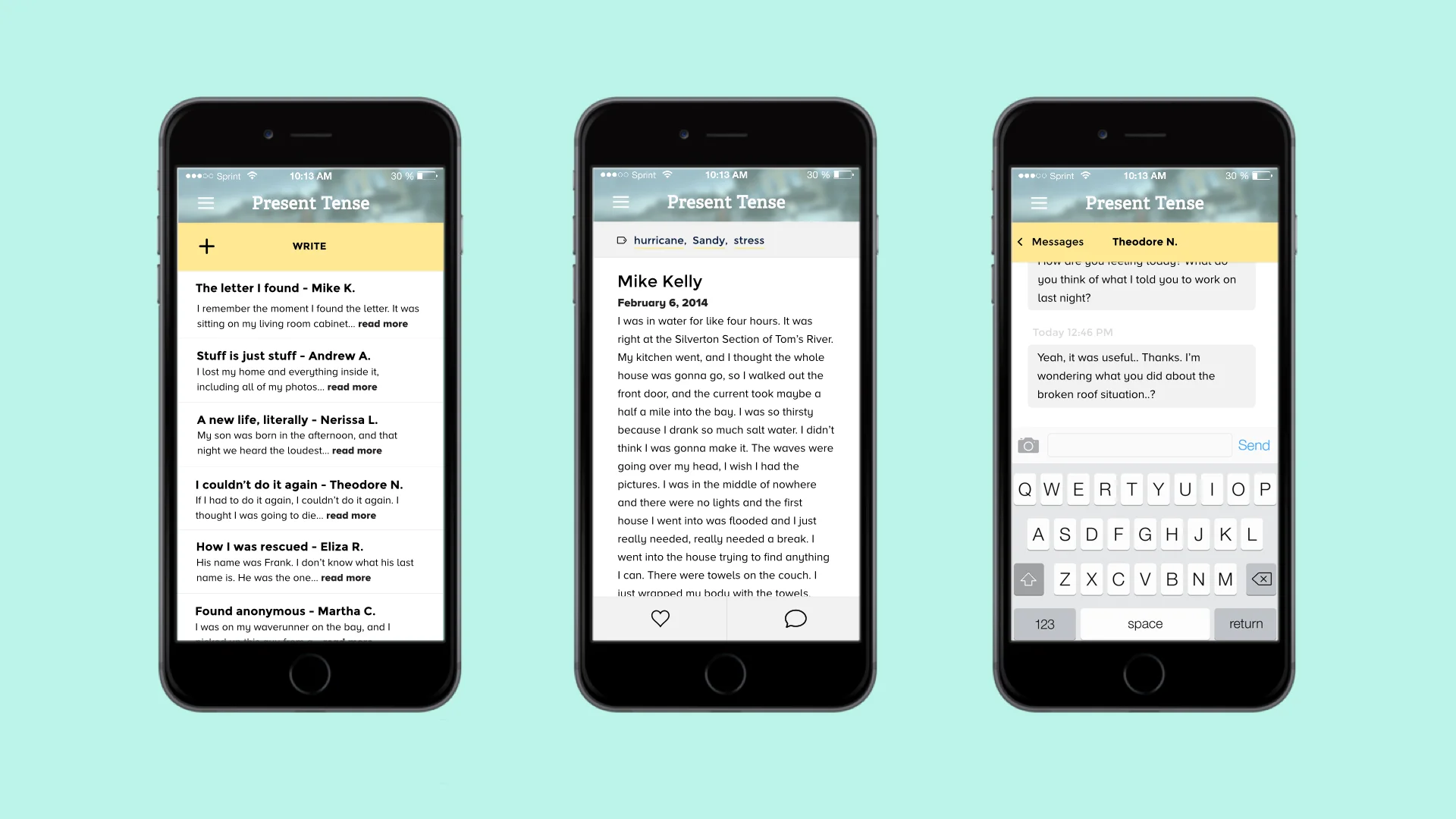

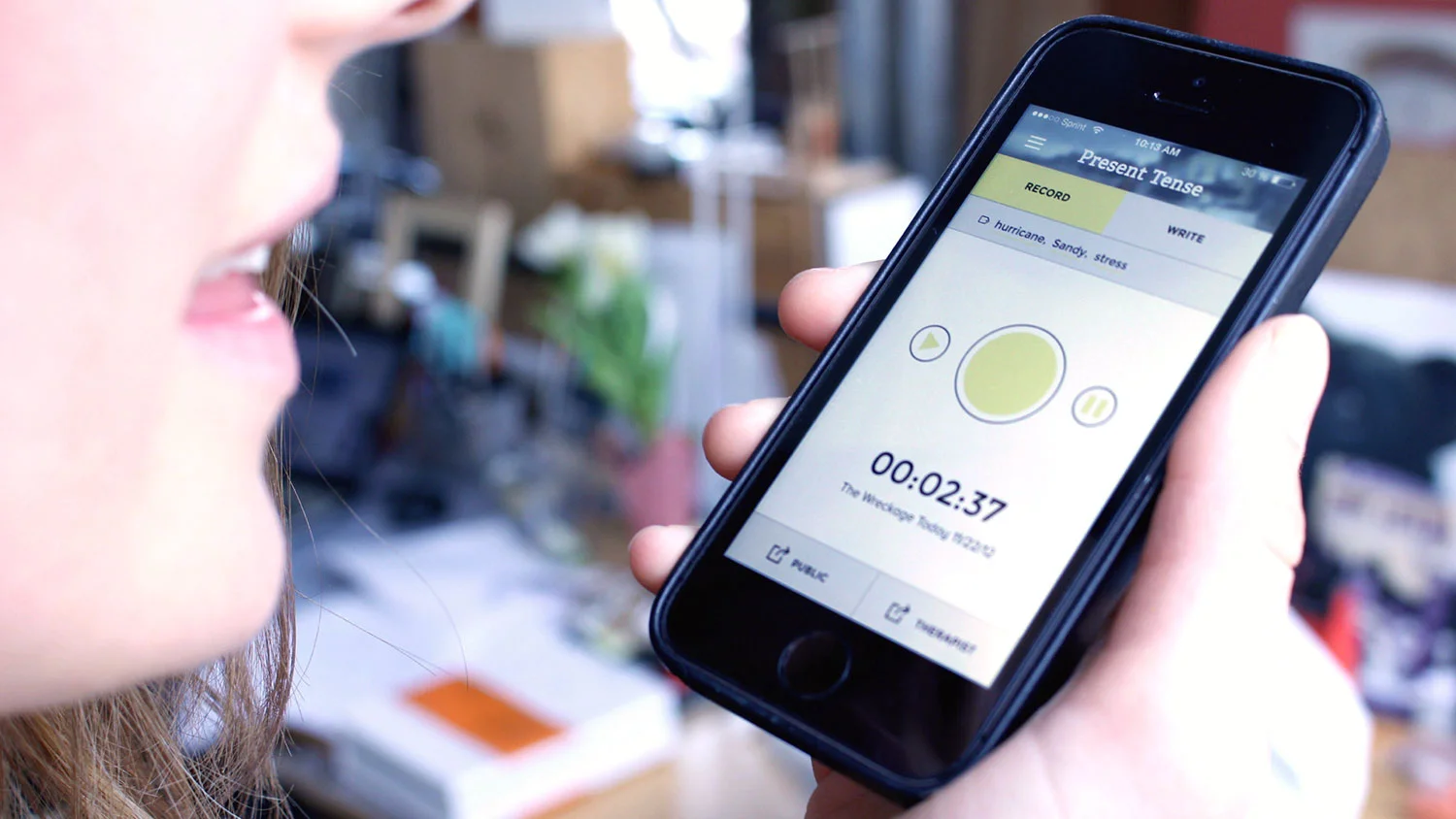

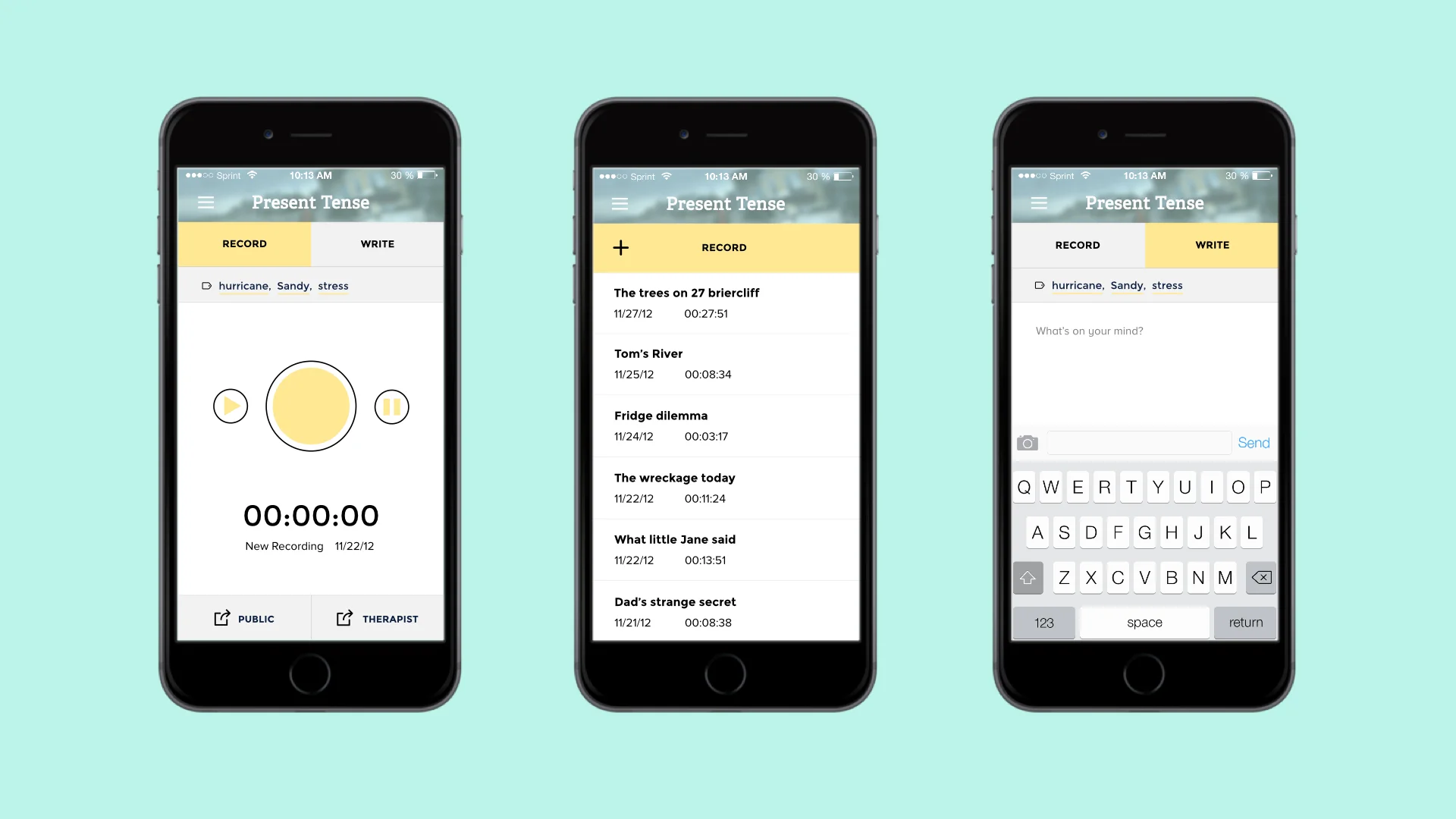

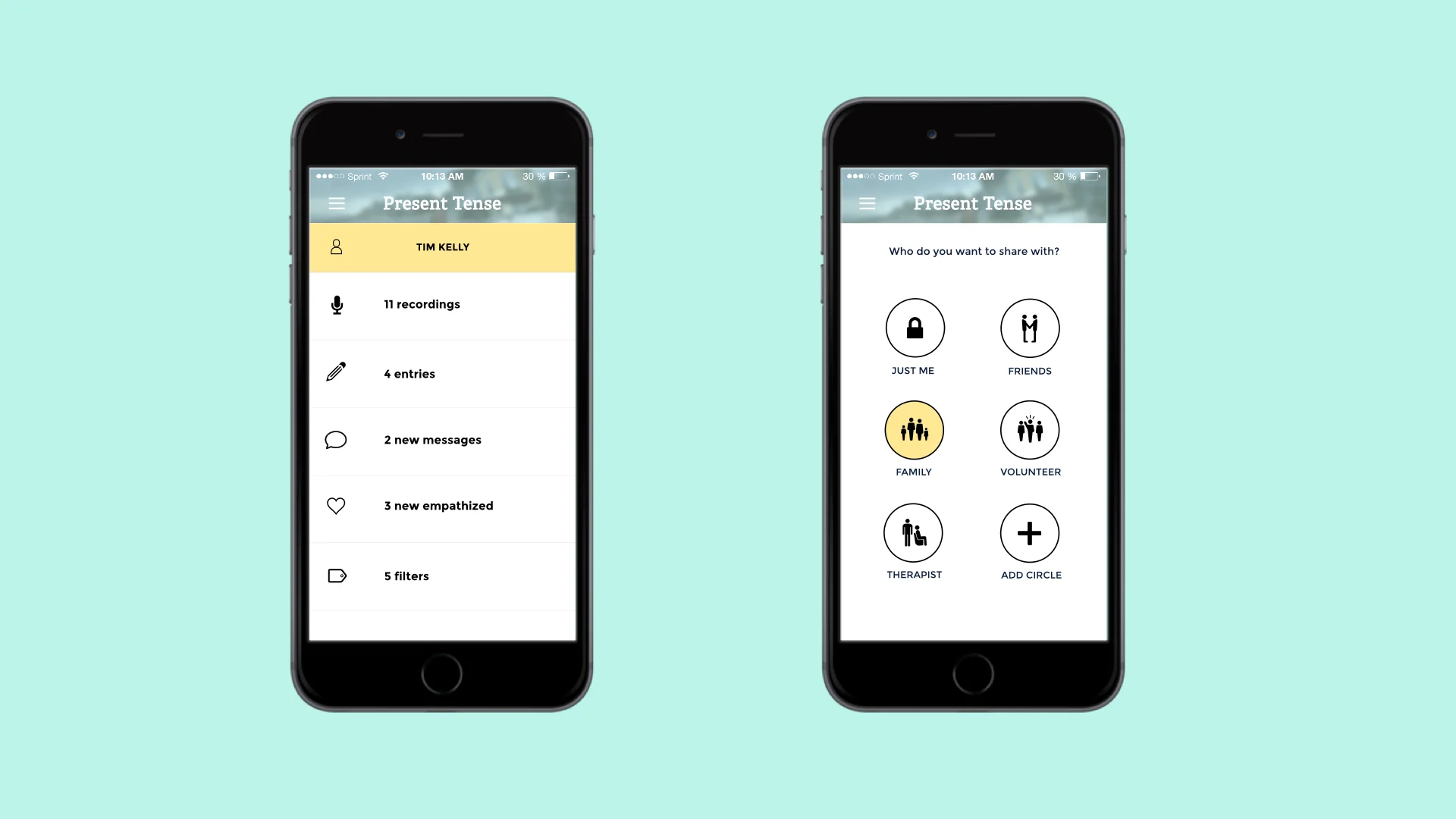

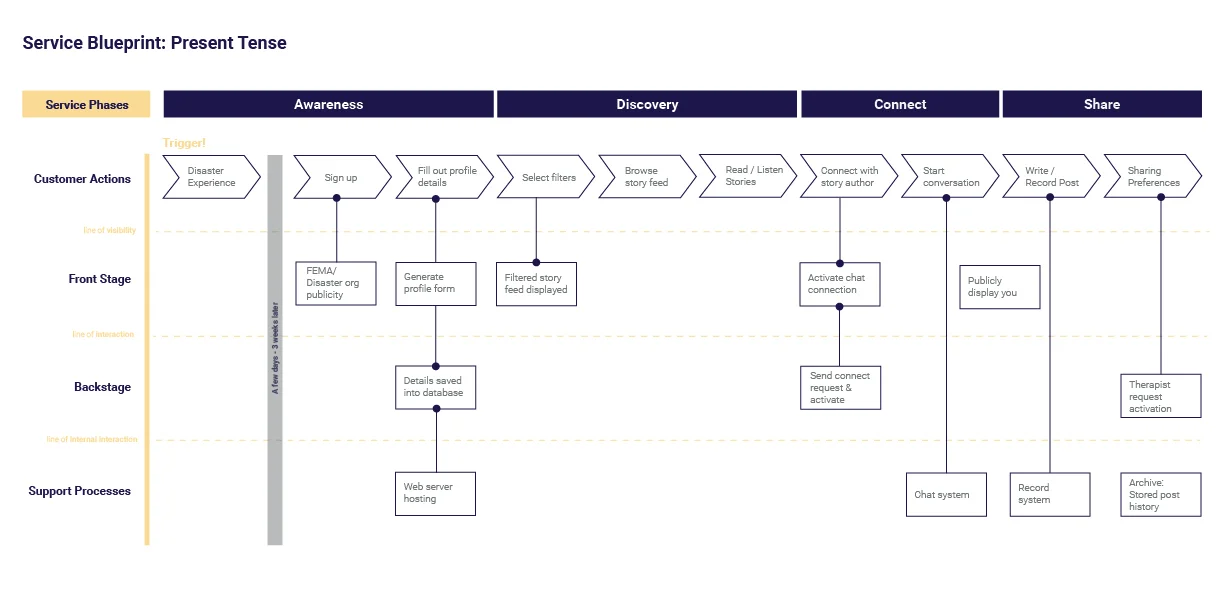

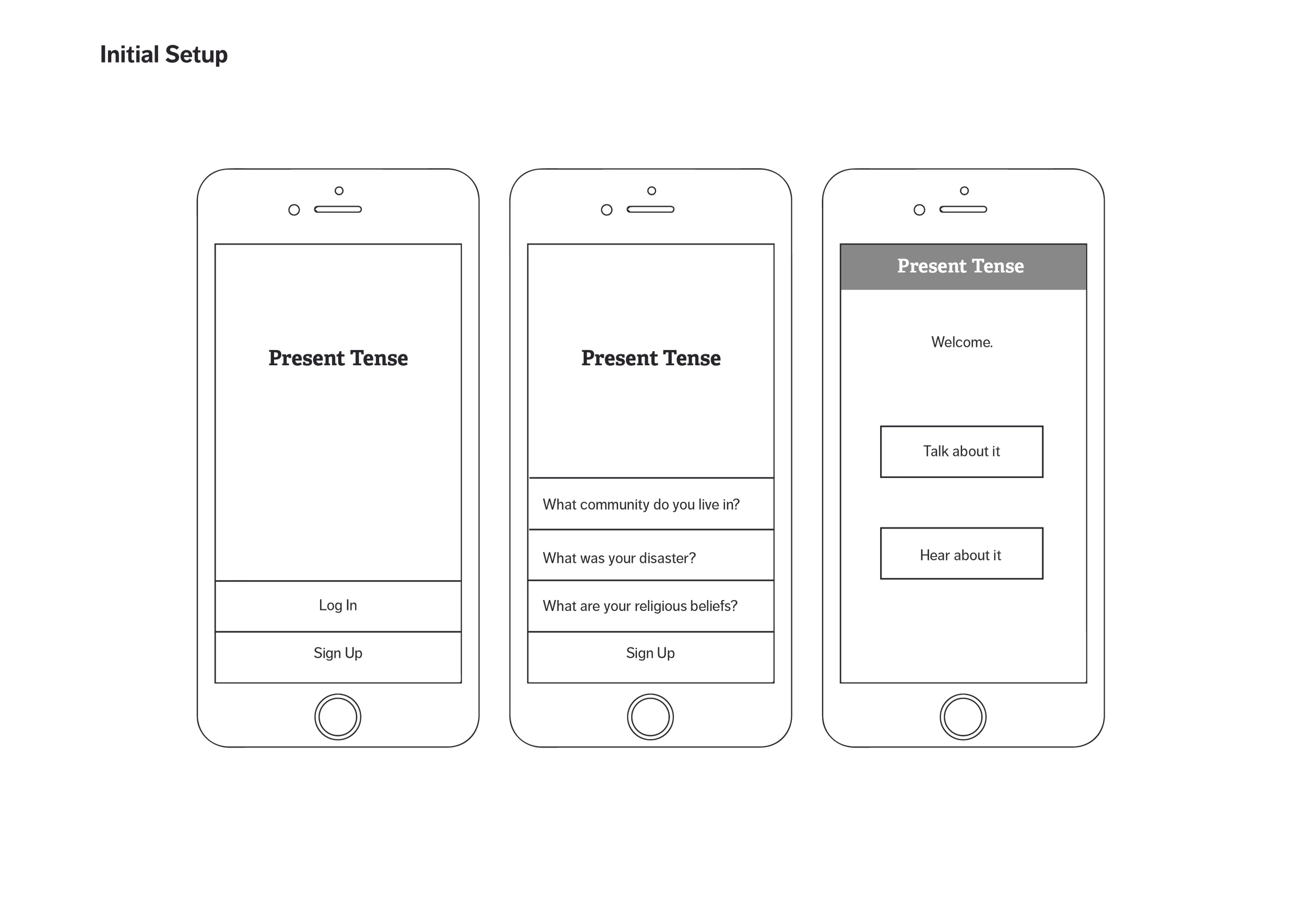

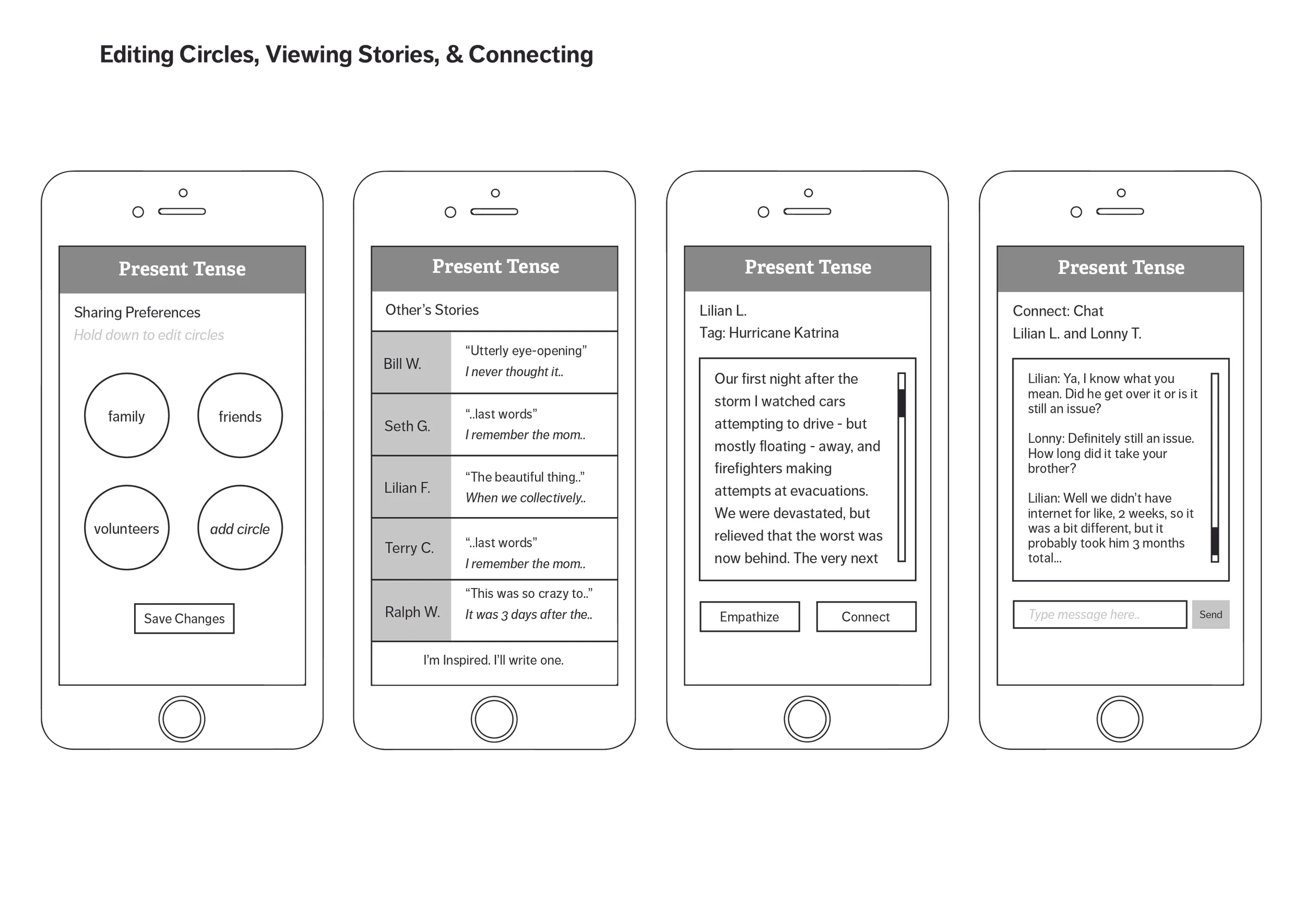

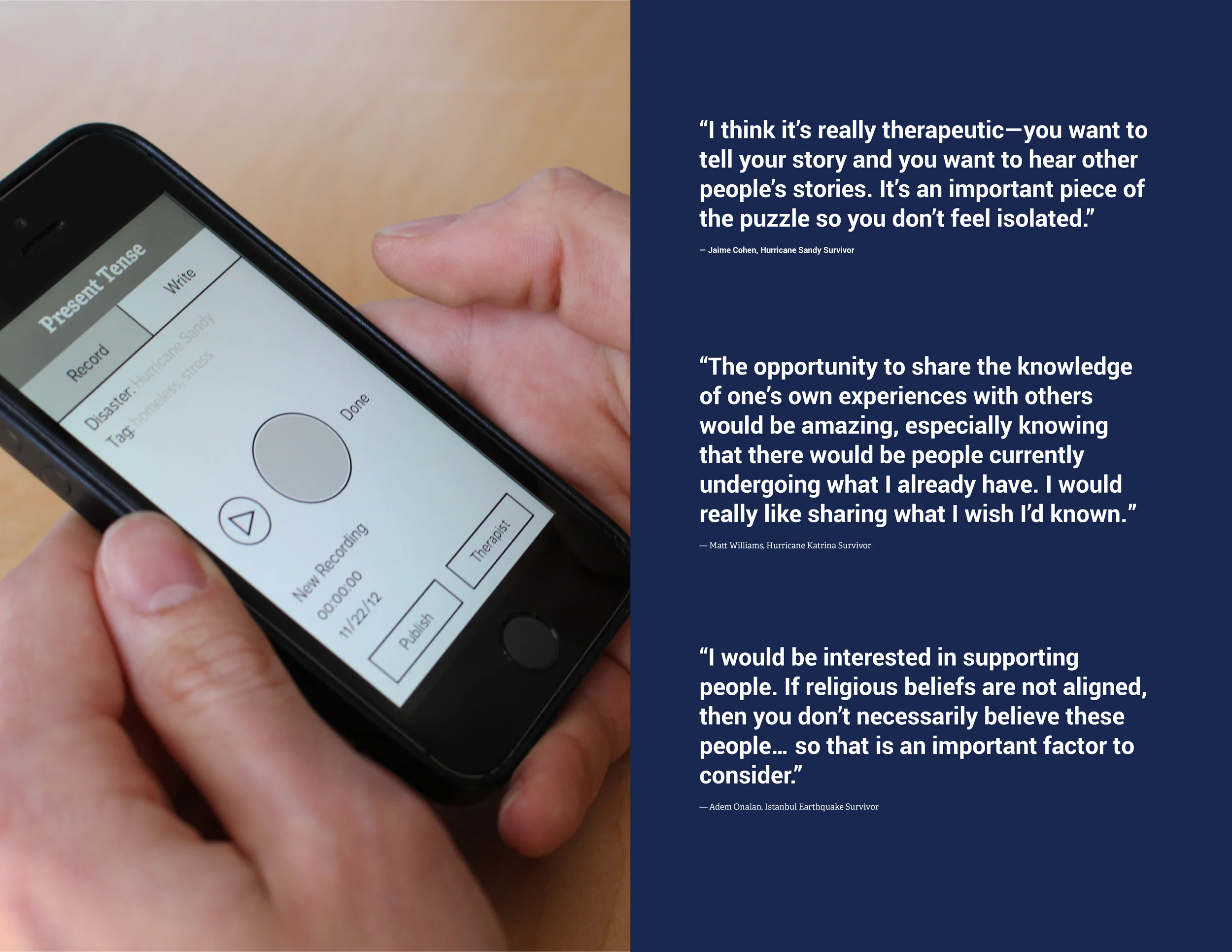

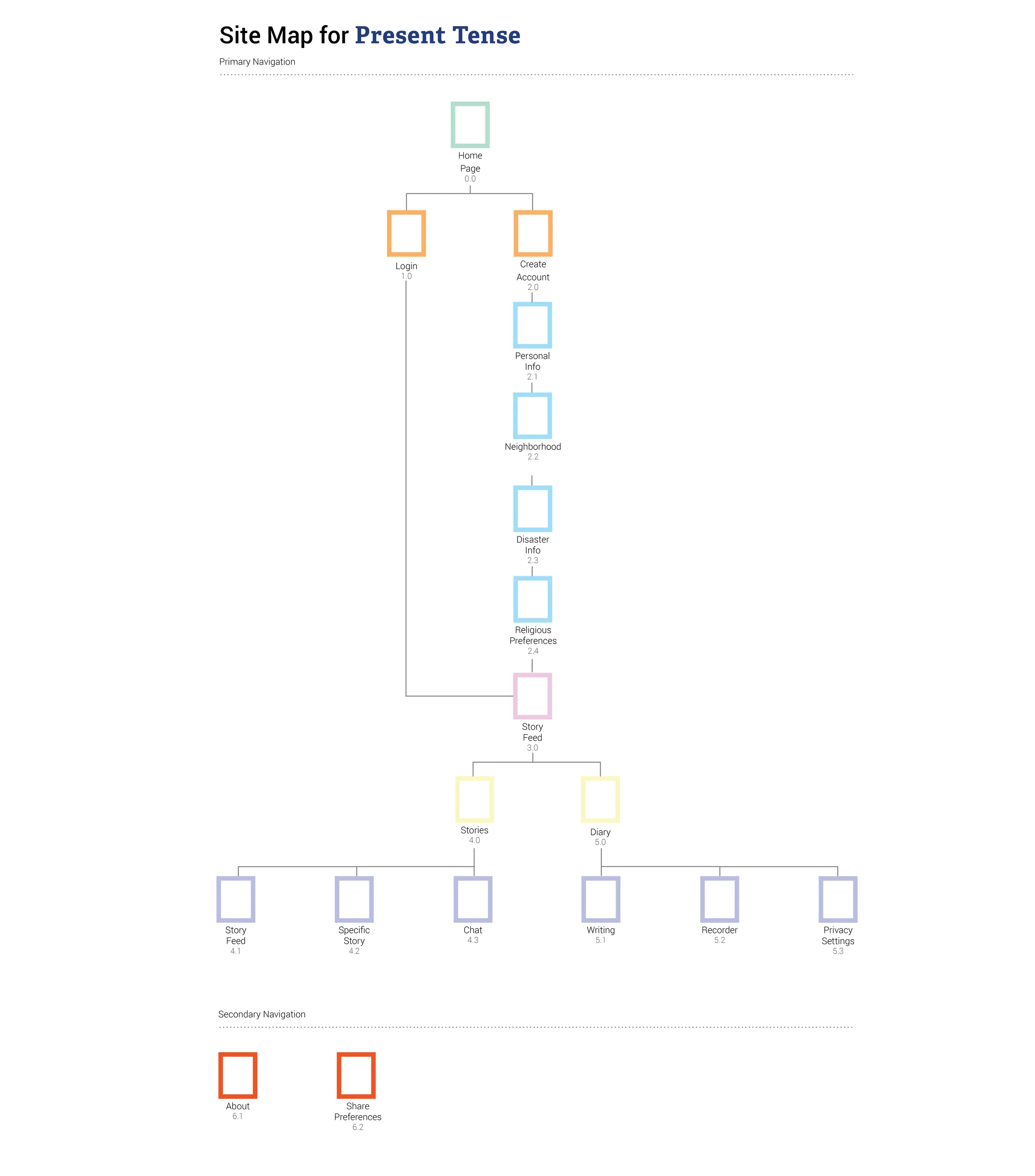

Leveraging the power of social problem solving and resilience building, in combination with healing by re-experiencing a traumatic event, Ayaydin developed the service Present Tense, a real time disaster story-sharing platform. Using information and filters about their neighborhood, disaster type, and beliefs, survivors can talk about and hear about other’s disaster experiences and connect with those they can relate to.

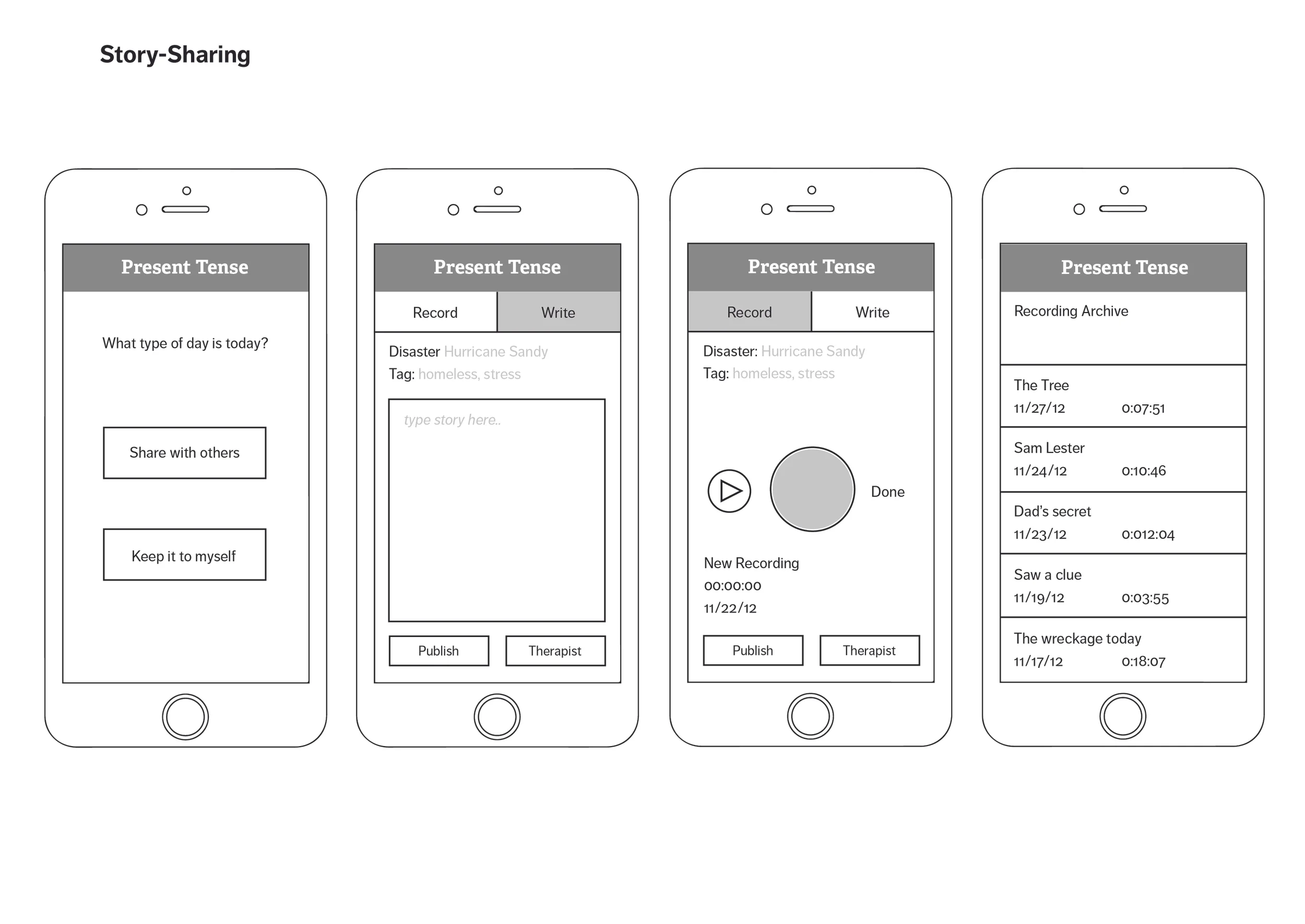

In addition to social sharing for healing, the platform is a place to deposit memories, creating an archive of recordings and journal entries for the survivor to reflect on. These entries can be kept to themselves, shared with the public, friend circles, or with a volunteer mental health worker who would provide instant support while having a holistic overview of their archived healing journey.

The service also promotes memory reconsolidation, which is the brain’s practice of re-creating memories over and over again. The very act of remembering changes the memory itself, so physically talking about trauma prevents the negative memory from being sealed over and repressed, which could lead to PTSD.

By harnessing the power of crowdsourcing and receiving funding from relief organizations, Present Tense will begin with one community’s disaster and expand into a nation-wide network.

UX/ UI Design process

The experience journey:

Final wireframes:

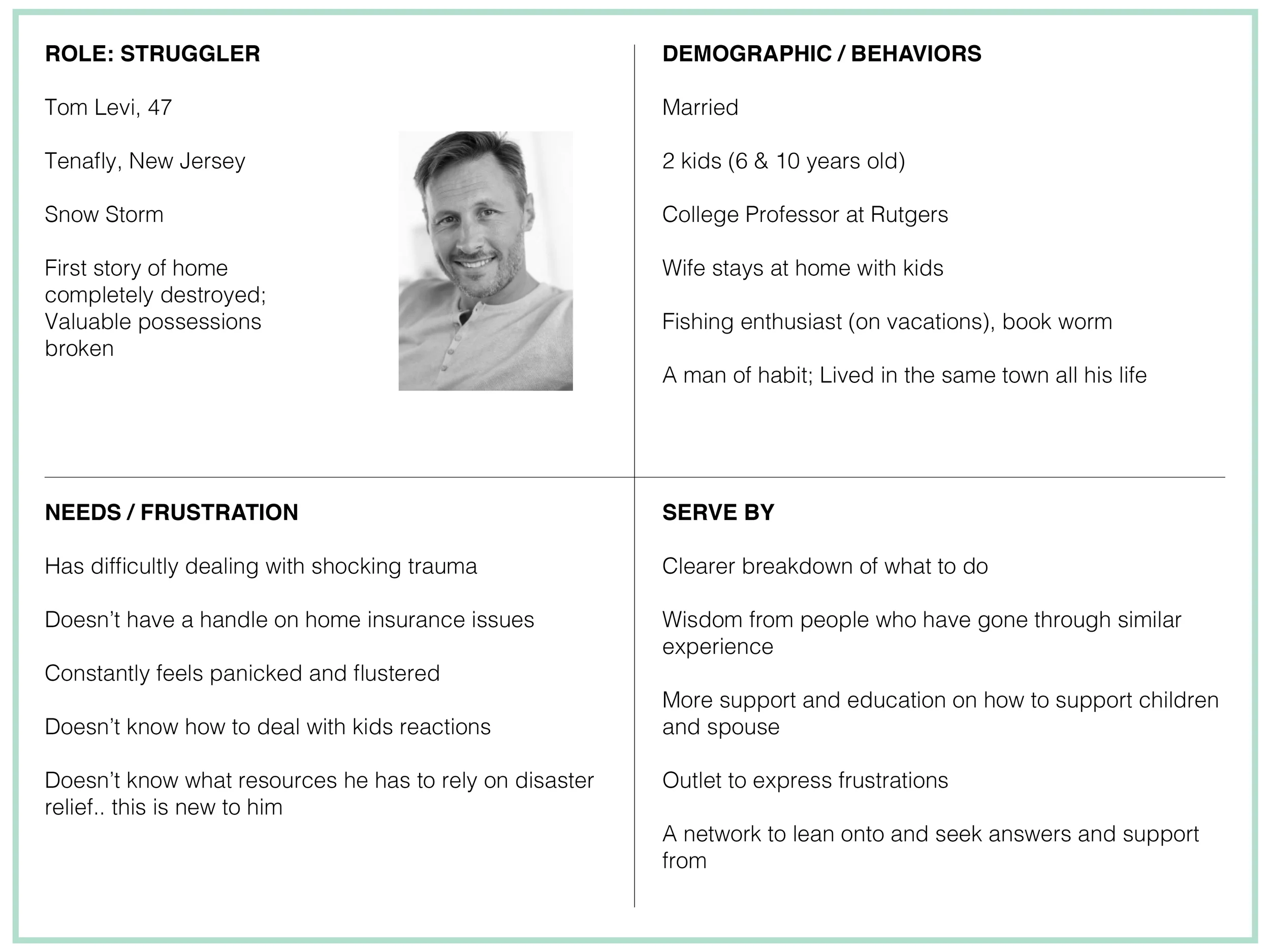

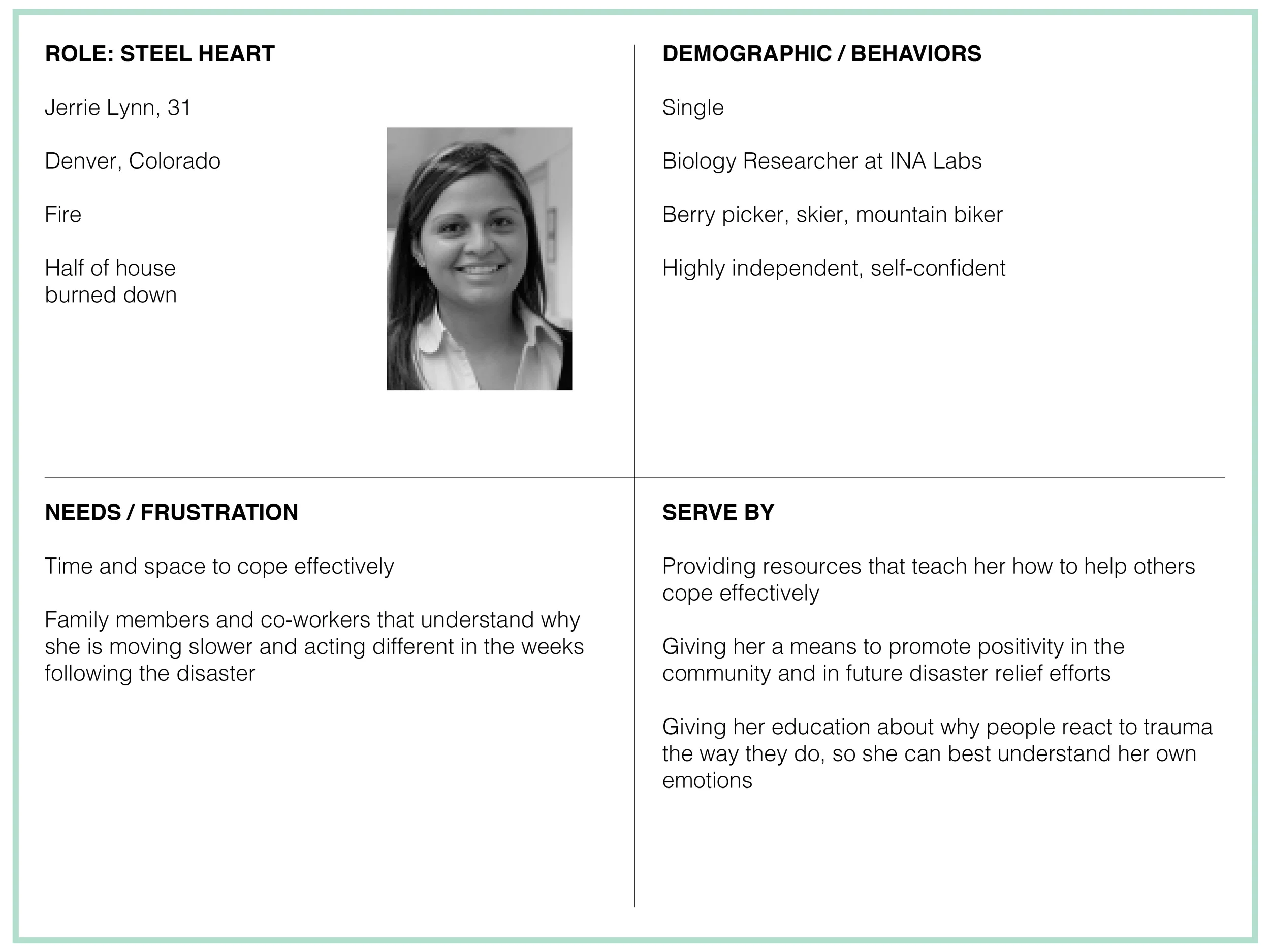

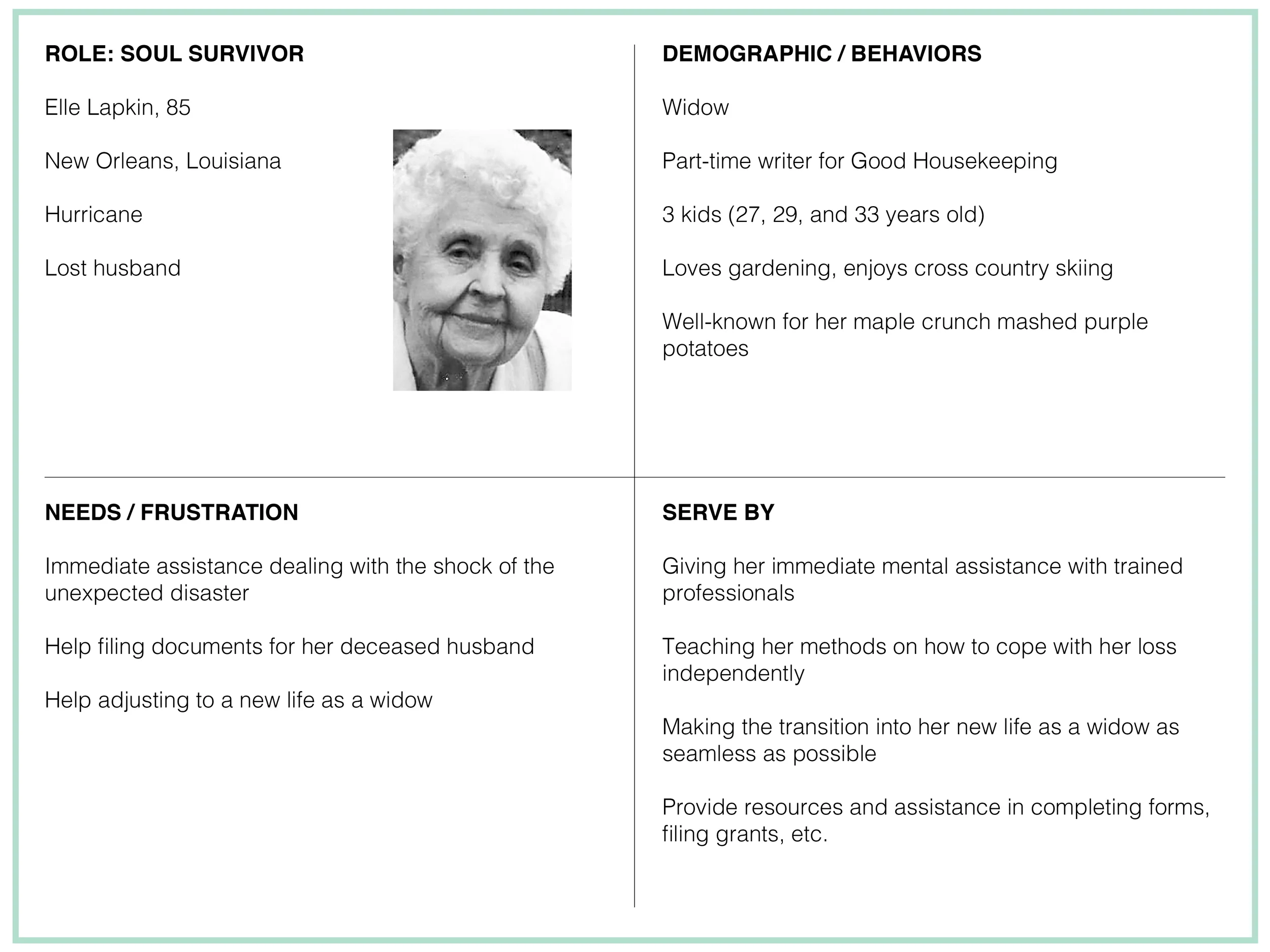

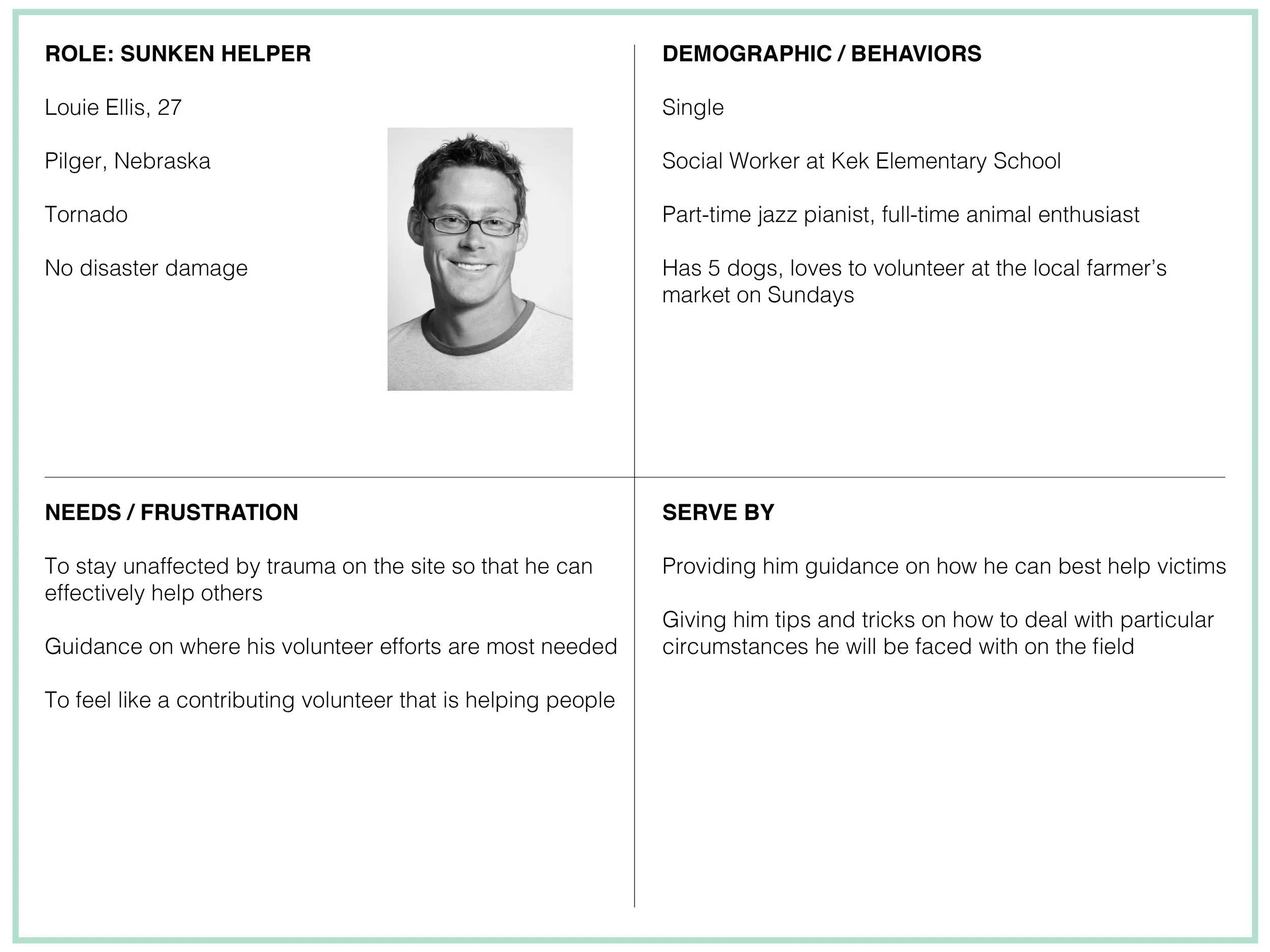

Persona development:

I started off by creating 4 personas as a representation of the goals and behavior of real disaster survivor types. I use these as a guidance when envisioning the future product offerings for mental relief. The Present Tense service has a place for all the users.

Experience Design

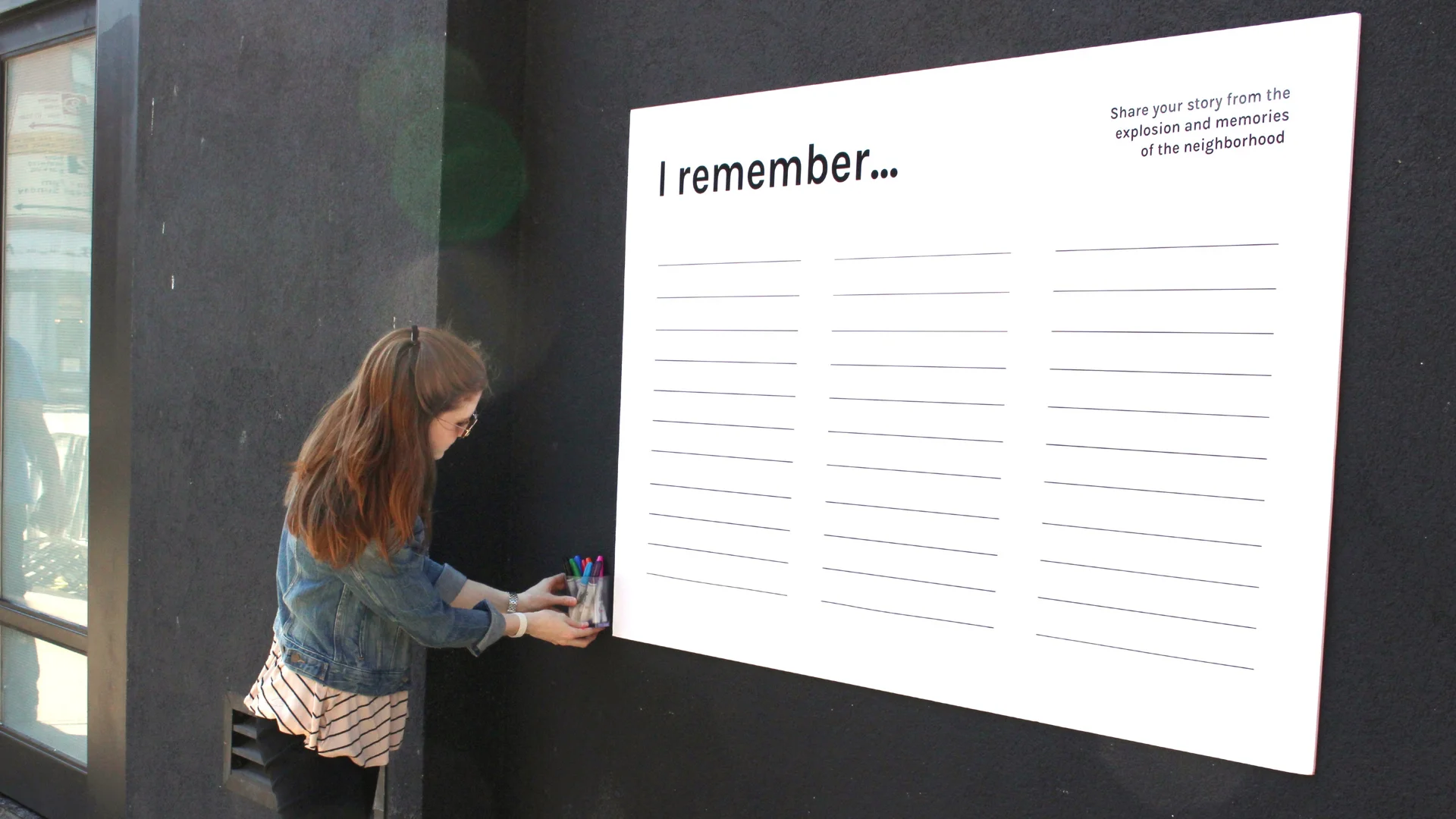

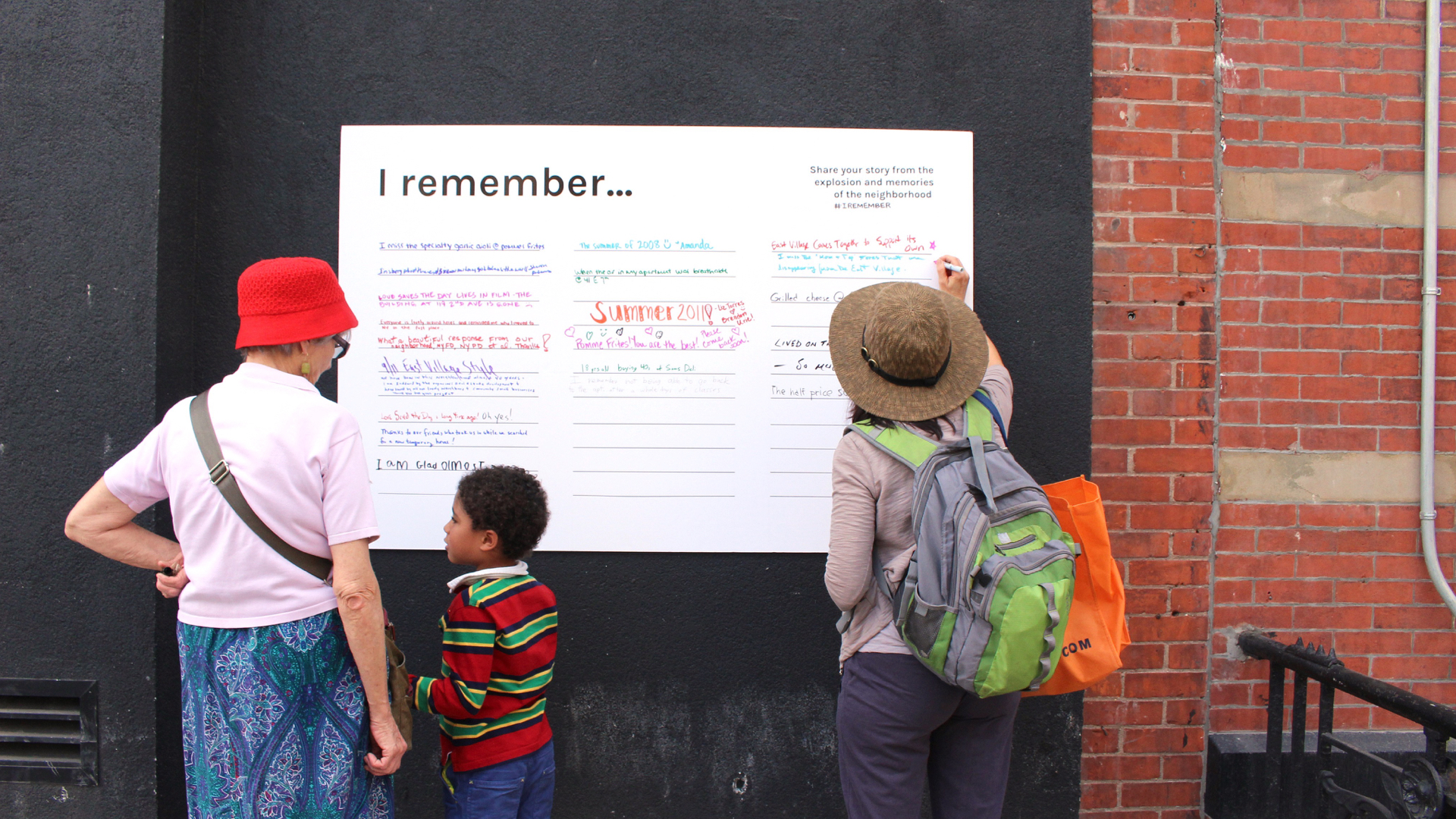

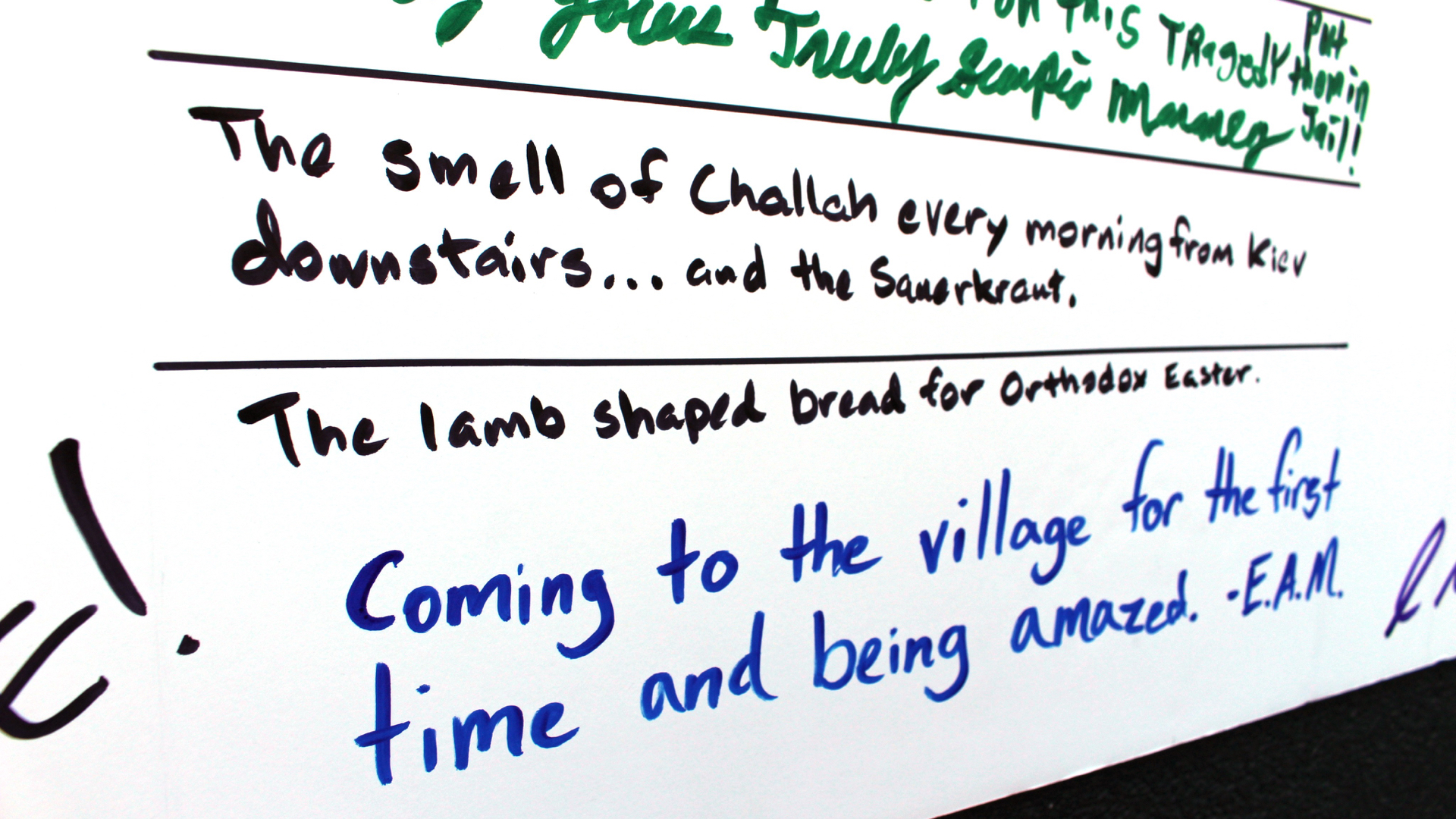

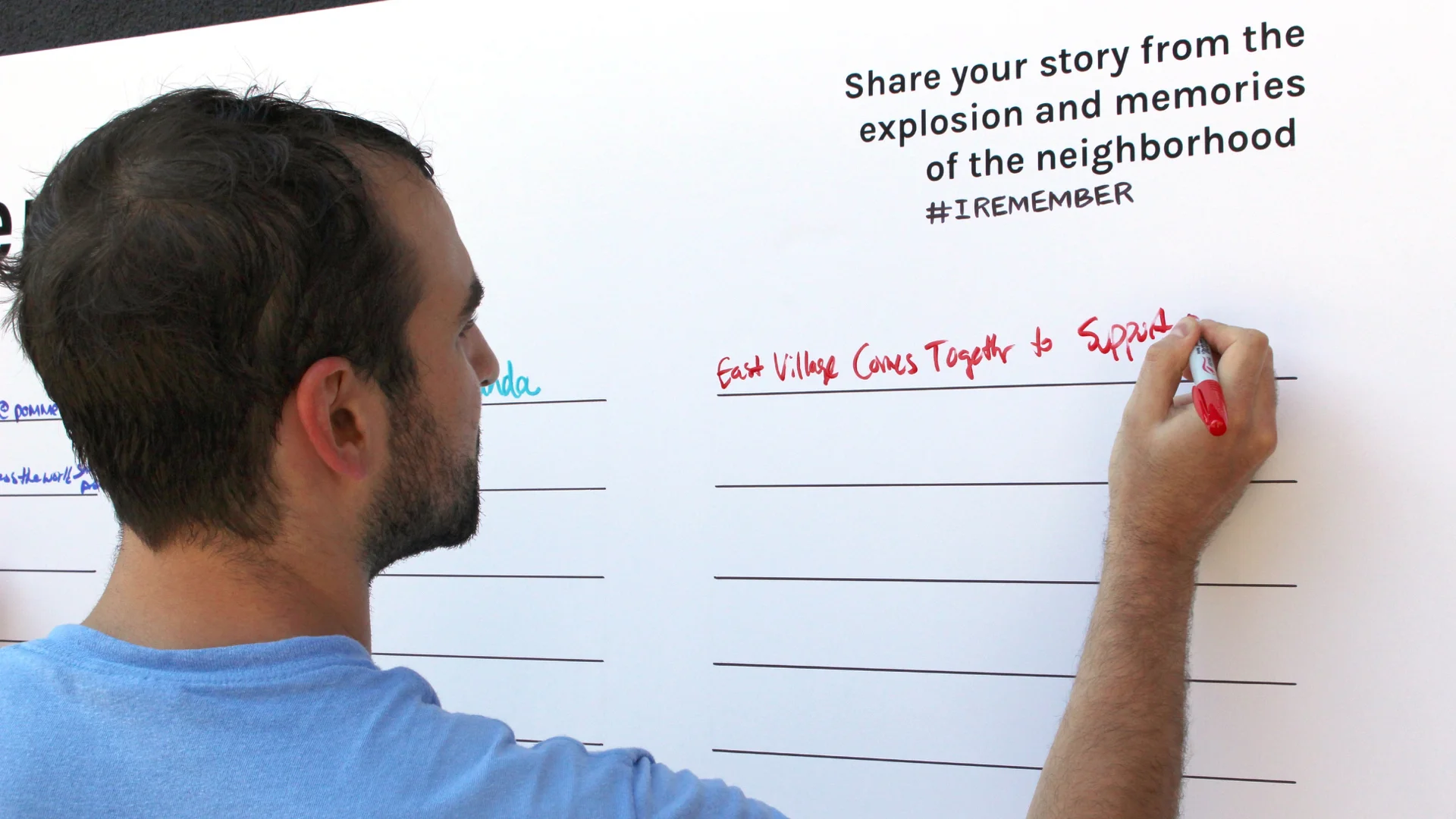

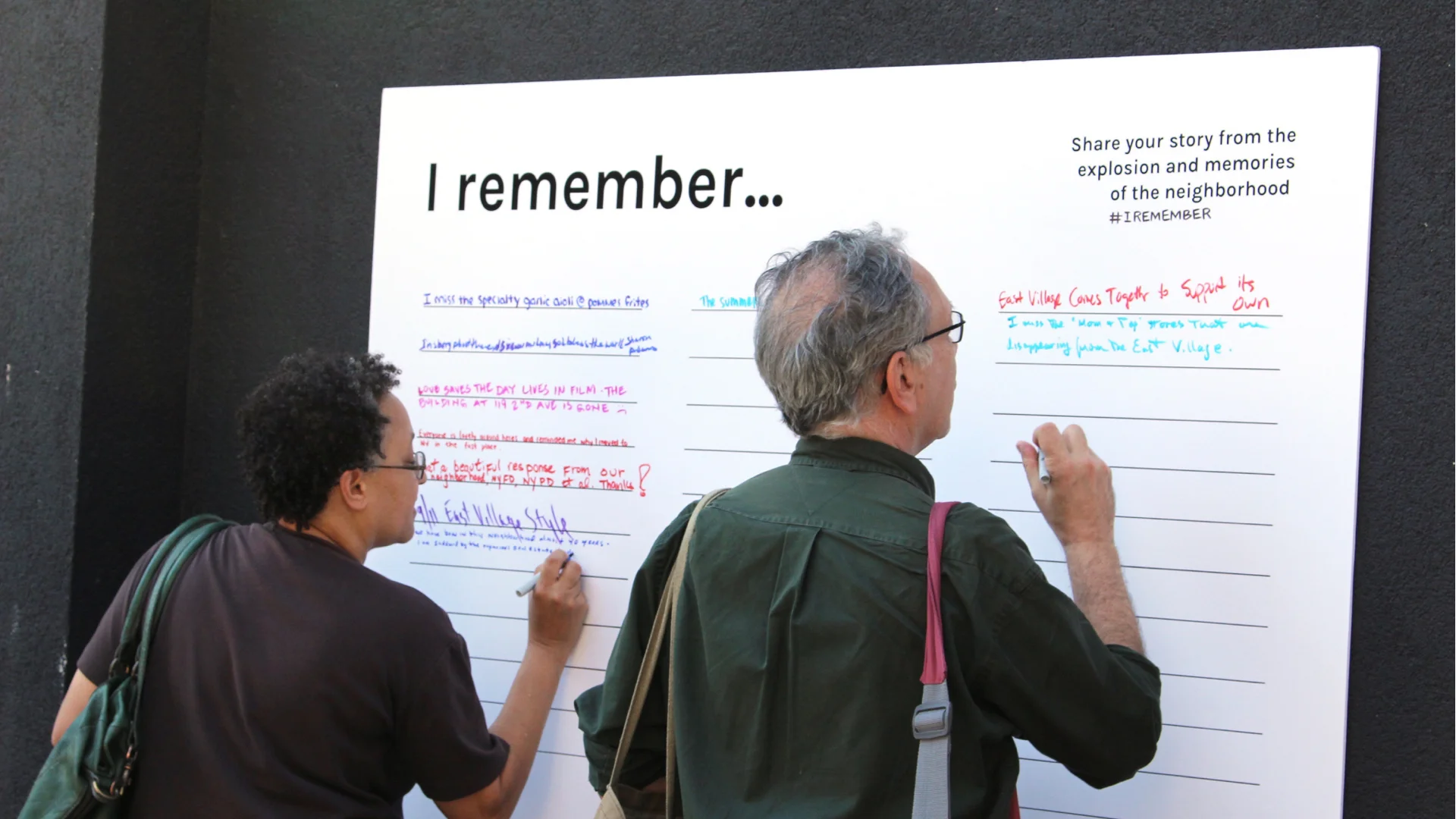

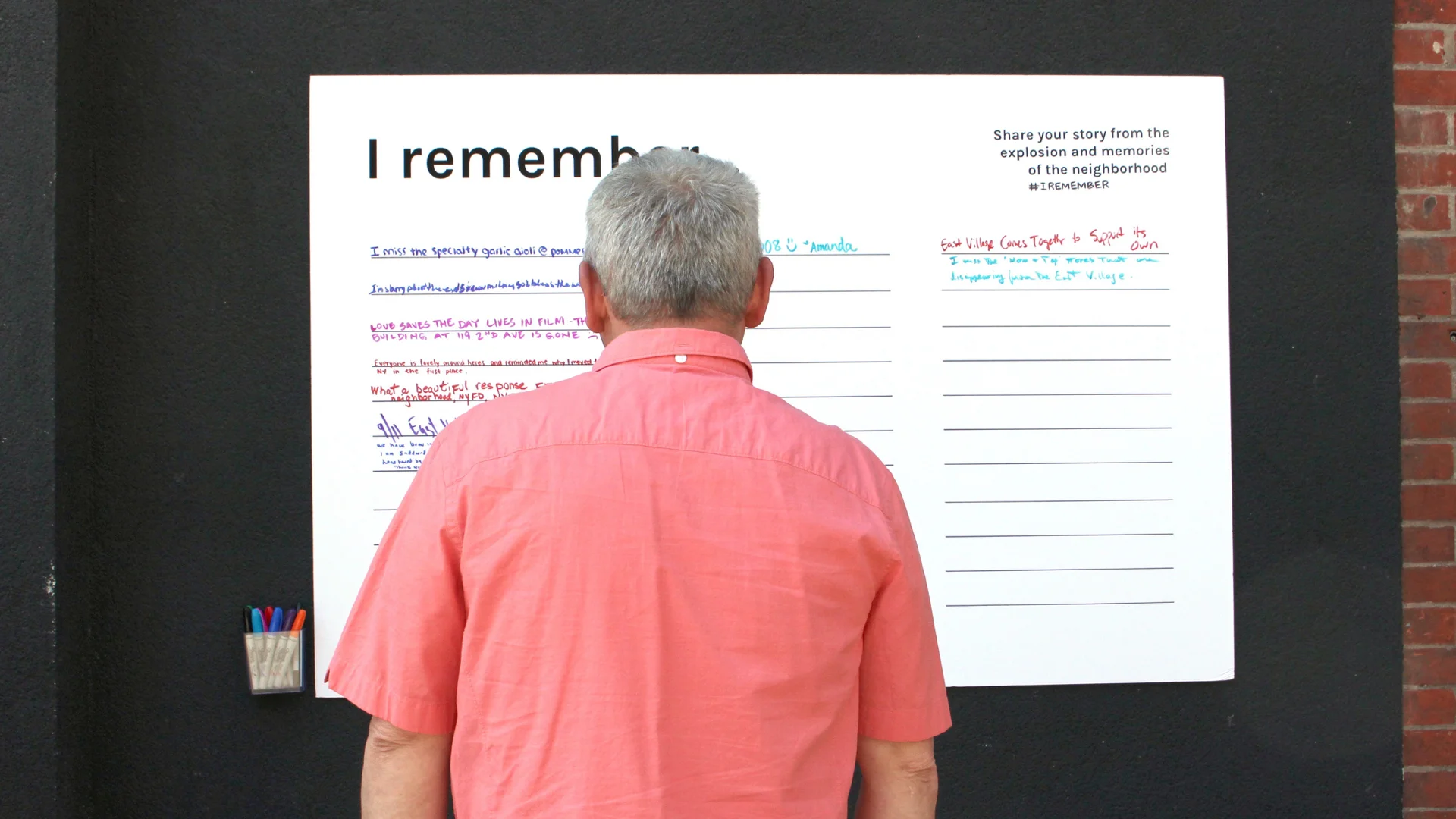

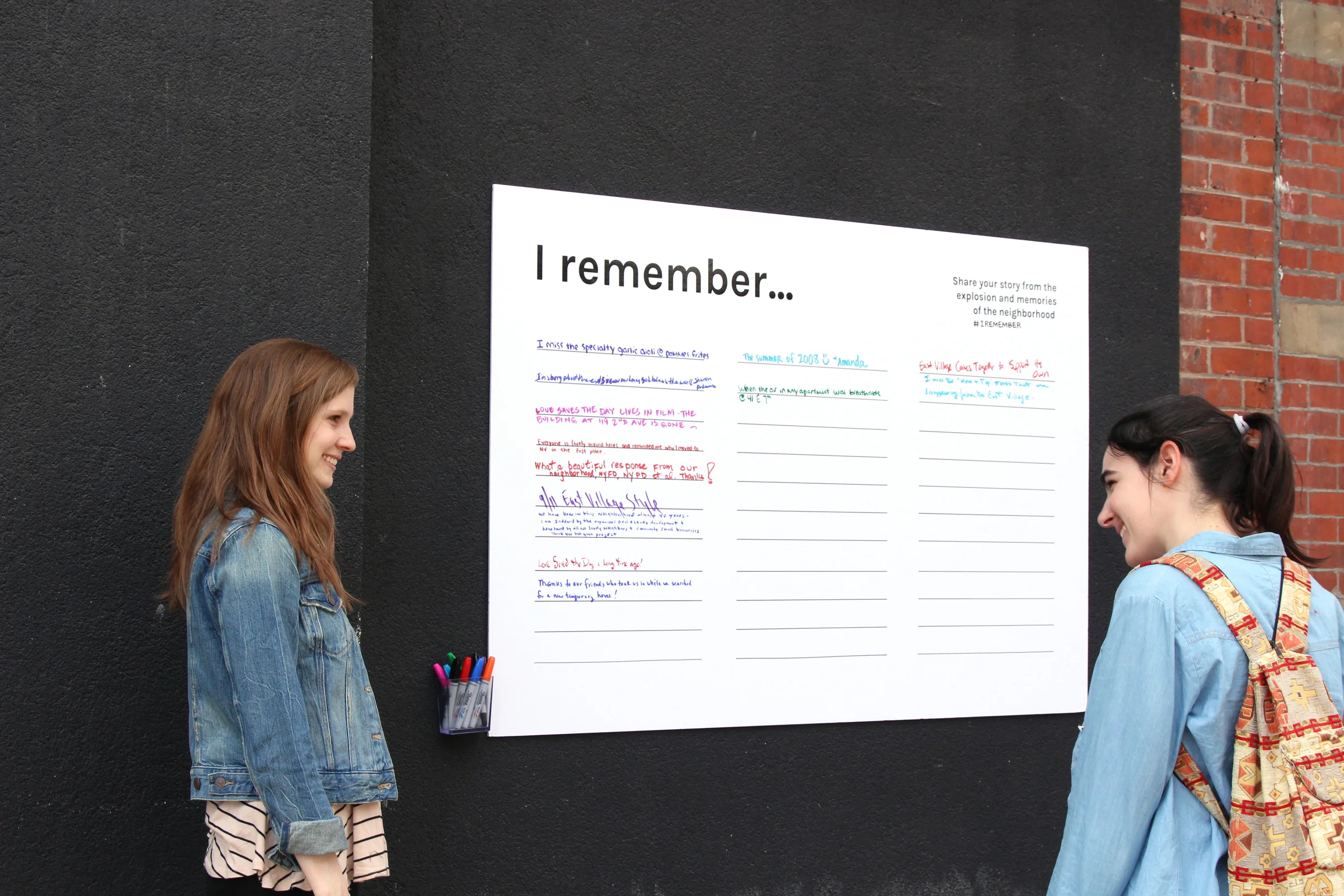

To test how effective sharing experiences a couple weeks after a disaster can be, Ayaydin designed an experience for a disaster closer to home. On March 26, an explosion in the East Village left a block up in flames, injuring 19, killing 2, and shocking the region. A few weeks after, Ayaydin posted a board across the street from the scene that invited people in the neighborhood to share their stories – general uplifting memories about the neighborhood or stories specifically from the explosion itself.

The piece prompts people to fill in the blank “I remember..” and it became a channel for starting conversations. People wrote memories, such as, “I remember getting on scene and having an immediate urge to help. Sad day.” One woman pointed across the street to the building facing towards the empty block and said, “You see the third floor window there? That’s my apartment. I still haven’t been able to move back in.” She wrote a note about how she’s thankful for the support she’s received from family and friends.

For part of the day, Ayaydin took a seat on a stoop close enough to see and hear what was going on, but far enough that no one would suspect she was associated with the project. Her absence gave passerby the permission to take time to view and add to the board without feeling pressured or judged.

People really spent time reflecting – reading and adding to the board – and turning around to acknowledge the vacant block where the exploded apartments, restaurants, and businesses used to be. Ayaydin validated her hypothesis through this experience, learning that reflecting, supporting, sharing experiences, and hearing other people’s stories are a way of mending pain and uplifting communities.

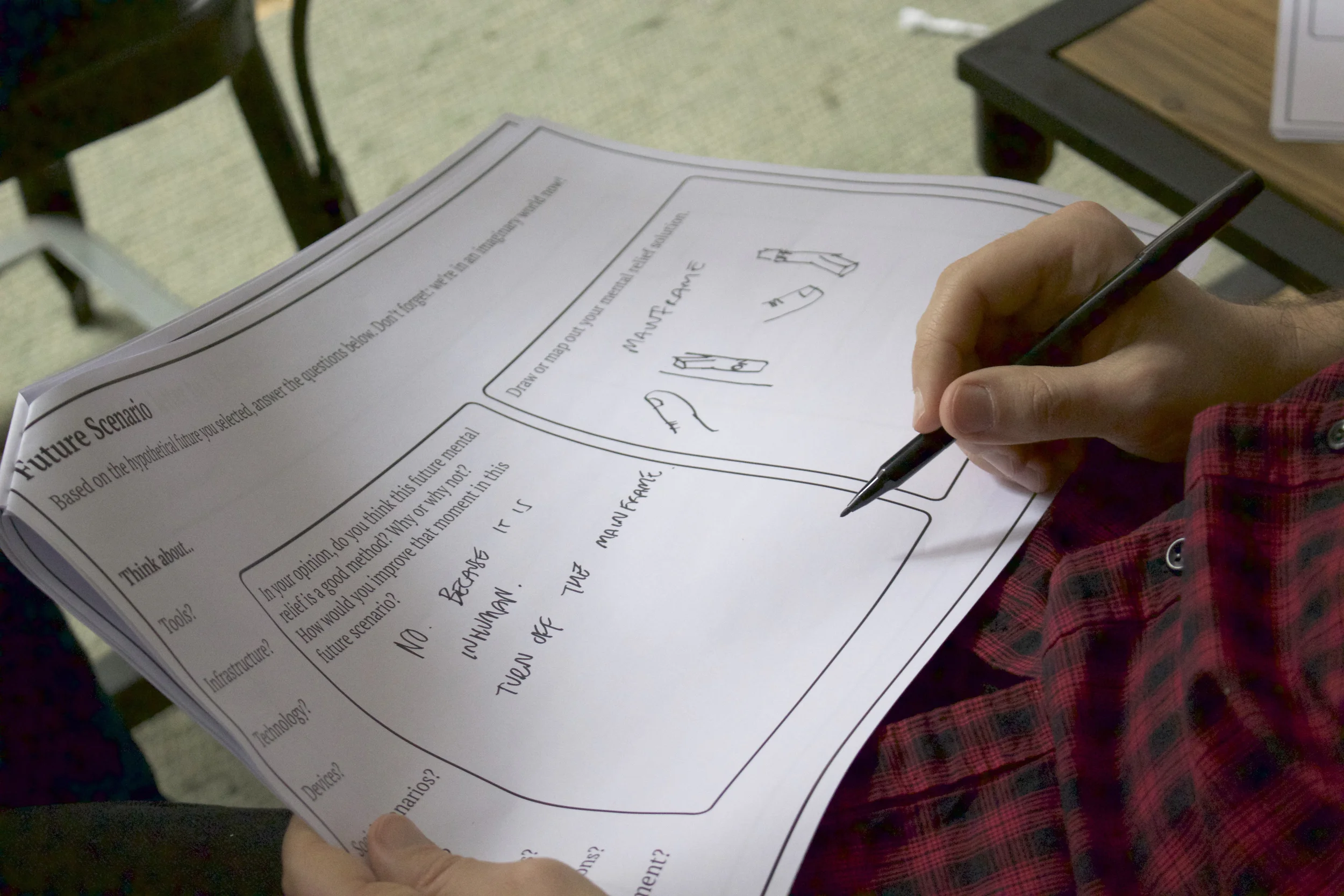

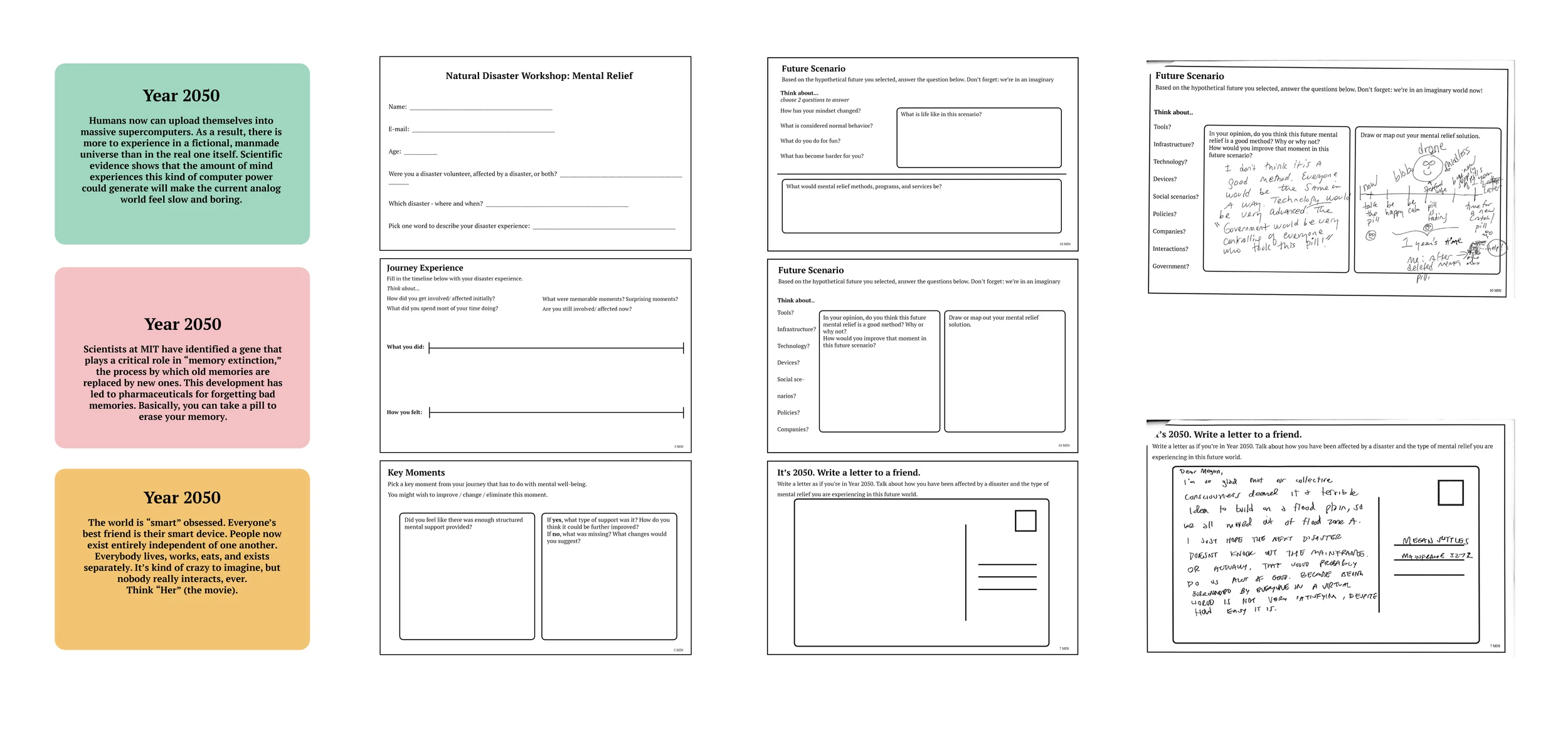

Co-creative workshop:

Leveraging the power of learning from real survivors, Ayaydin created, designed, and facilitated a co-creative workshop with 9 disaster relief victims and volunteers in the NYC area. With the goal of generating ideas about what the future of post-disaster mental relief could be, the most valuable insight was that very few saw value in painful memories shaping their identities and most would ideally like to forget them forever. From this, Ayaydin inquired if she could design an object, a ritual, or a behavior to help trauma sufferers forget the memories they so badly want to erase from their lives.

Futuring & Speculative Design

Process:

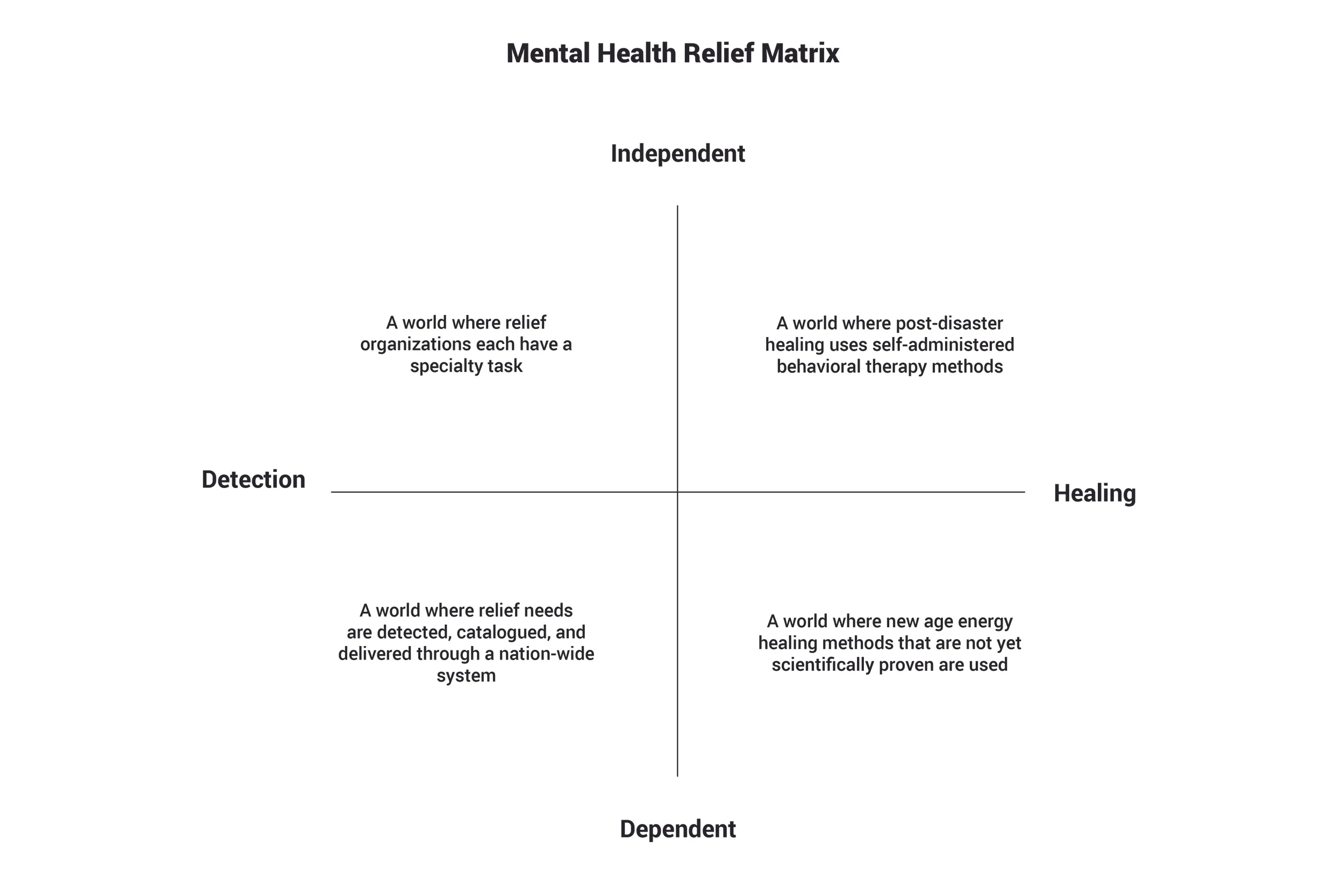

The future of the thesis territory was framed by creating a two-by-two matrix. The purpose of building a narrative of these potential futures is to provide a context in which to think about what types of objects could exist in the future.

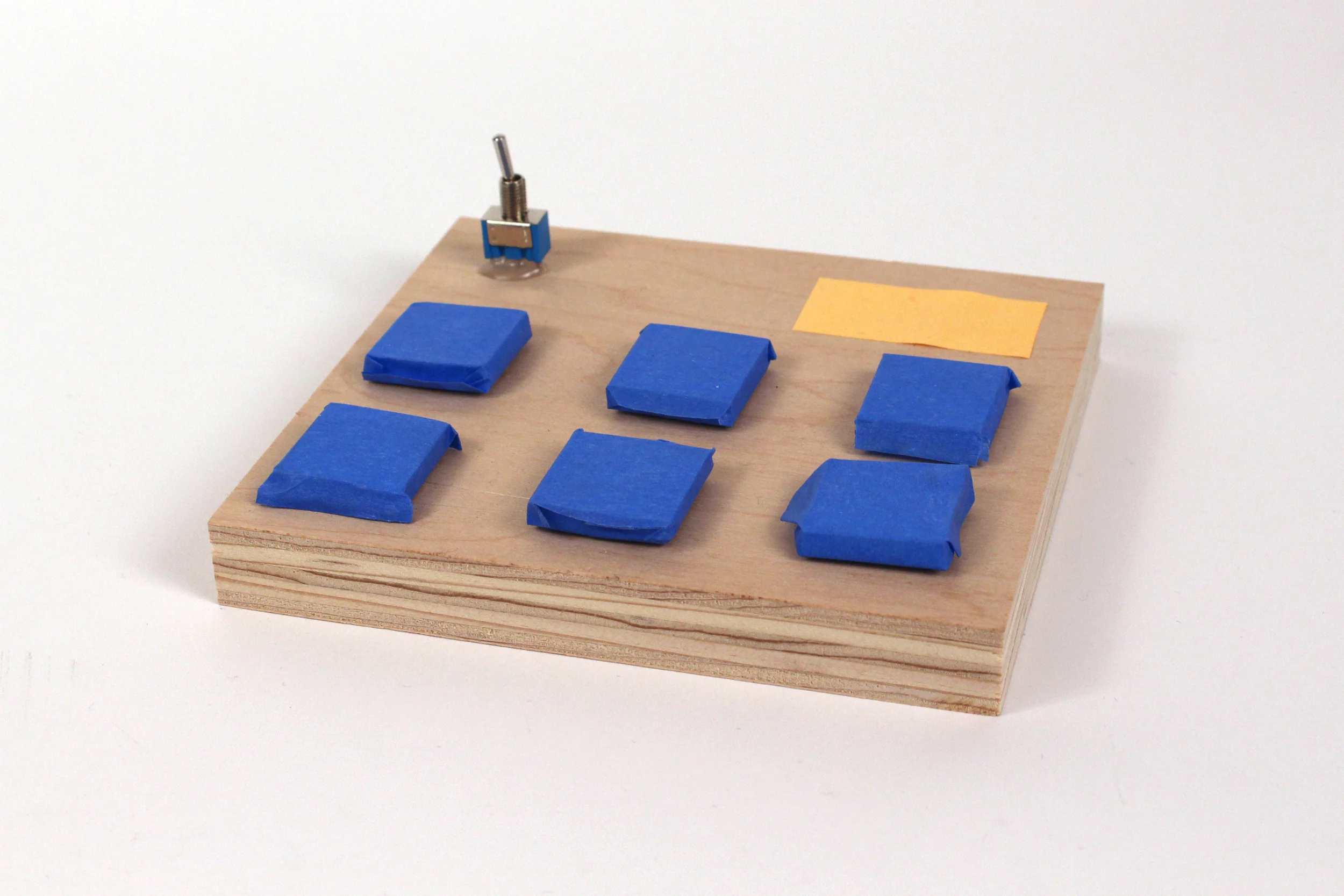

The design led research process involved building quick hack prototypes using found materials and items from dollar stores to make discoveries and conduct tests through physical forms. The first iteration was 2 tools that fit into each quadrant. The second iteration was refining one idea for each quadrant.

Final object development:

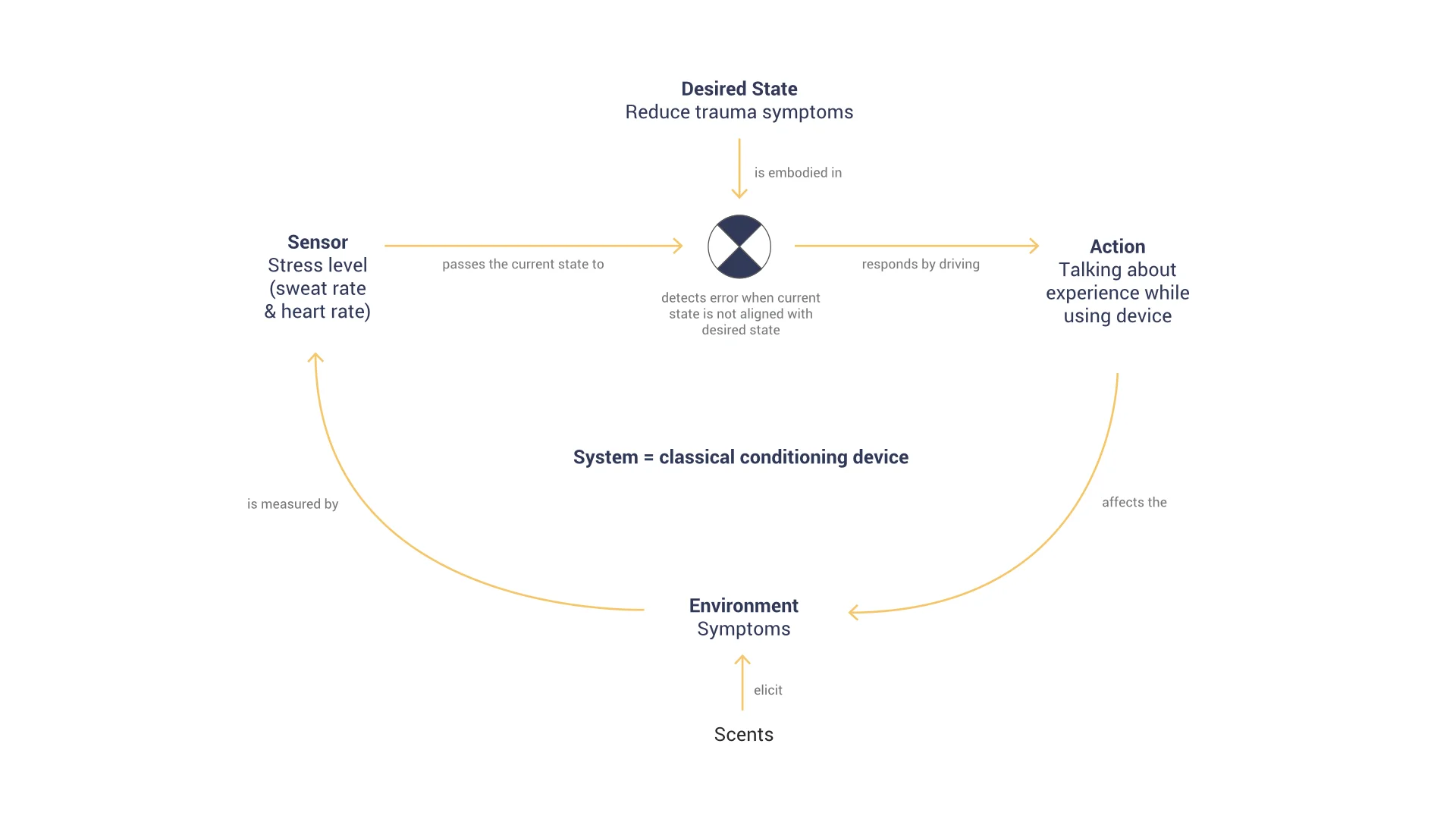

Contemplating the future of healing, Ayaydin explored ways she could re-contextualize behavioral therapy methods into self-help tools. Currently, therapists desensitize patient’s responses to memories using behavior modification techniques based on classical conditioning theory, which is when you learn a new behavior via the process of association. Essentially, two stimuli are linked together to produce a new learned response.

How the object works:

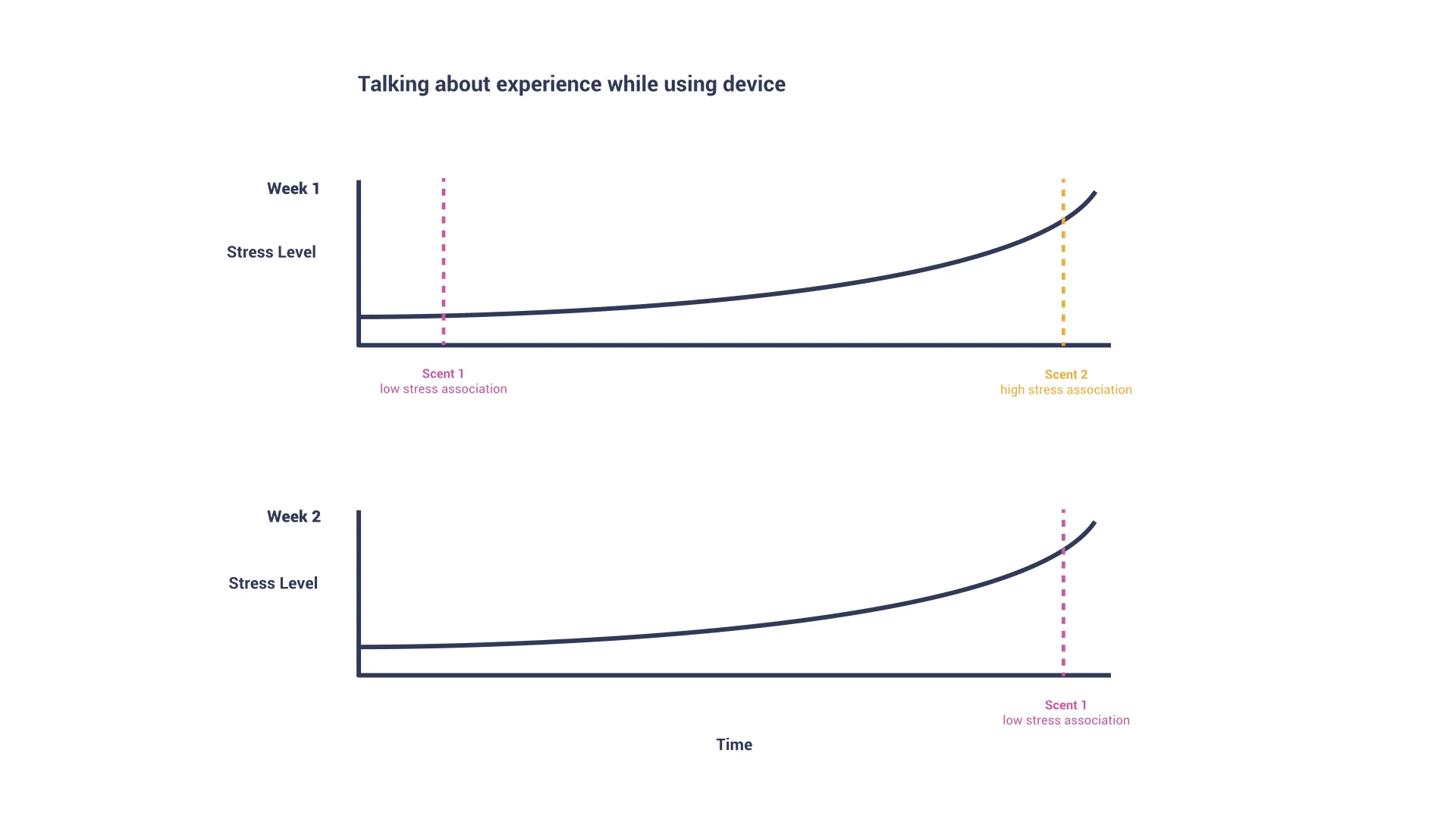

While a survivor talks about their experience, their stress levels are detected using a heart pulse sensor. By training the person to associate particular scents with specific levels of stress, and intentionally changing those stimuli at appropriate times, the device will help the person to re-learn their traumatic memories with new reactions. For instance, when the user is highly stressed, the scent they’ve learned to associate with low stress is emitted, re-wiring their brains to associate the most traumatic moments of their memory with calm physiological reactions.

Conclusion

After all her research and design explorations, Ayaydin pulled the pieces together and made an interesting discovery. Regardless of the scientifically proven theories or tested methods of coping, a person’s life values, religious beliefs, spirituality –whatever it is that they live by – have the biggest impact in how they will heal. She heard it from many different people in unrelated contexts, and each of them offered a unique interpretation and perspective.

Ayaydin’s conclusion is that everyone was there when something happened – he was there when, they were there when, even you were there when something potentially traumatic and certainly impactful happened in your life. What Ayaydin thought was so objective - figuring out the optimal solution for mental relief - turns out to be completely subjective.

Having learned this, the designer leaves us with I Was There When – an exploration to get us one step closer to understand how people can cope with trauma through a set of concepts, artifacts, experiences, and ideas that she passionately studied and carefully crafted in a way that each individual trauma sufferer can apply to their lives in their own unique ways.

Personal Designer intent:

As a designer with a background and keen interest in psychology, I bring both sides into my work by designing tools that drive behavior change. The study of human behavior gives me the access and permission to use scientific findings, and design gives me the power to activate and engage with a larger audience.

Elliott Montgomery, a professor of mine, once said, “science is the study of what is now, anthropology is the study of the past, and design is the study of the future.” No matter how much we learn and know about humanity yesterday and today, design is the tool that informs tomorrow. This makes designers a unique tribe of change-makers.

The type of change I want to make lies in helping other people become their own change-makers. French product and architectural designer Philippe Starck says, “designers of the future will become coaches. They’ll be helping people design their own lives as we move towards the service economy.” My thesis work is an attempt to coach people to take the reigns and create their own happiness in their lives.